The post What Is Rabbinic Judaism? appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>[EDITOR’S NOTE: The following article was written by A.P. auxiliary writer Dr. Justin Rogers (Ph.D., Hebrew Union College–Jewish Institute of Religion). Dr. Rogers is Dean of the College of Biblical Studies and Professor of Bible and Judaic Studies at Freed-Hardeman University.]

Most American Christians are undereducated on the beliefs and practices of their religious neighbors. As the American religious landscape becomes increasingly diverse, it is wise for Christians to learn about the groups that surround them. A basic understanding of the world religions makes us more sensitive to the beliefs and practices of our neighbors and equips us to reach others with our faith and to defend the Truth “with gentleness and respect.”1 We will attempt to survey in this article the foundations of one world religion, the smallest of the so-called “three major world religions,” Judaism.

Modern Judaism is only partially based on what Christians call the Old Testament.2 Personal piety came to replace sacrifice in Judaism long ago, in texts like Midrash Leviticus Rabba, which suggests a life of spiritual sacrifice is just as efficacious as a blood offering. Therefore, asking why Jews today do not sacrifice is evidence of an unawareness of their beliefs and practices. Like Christians, Jews recognize the authority of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, but they also recognize the validity of later traditions and texts. Just as modern Catholicism draws on centuries of traditions that Catholics affirm as authoritative, so also modern Judaism draws on traditions passed down through the centuries through the rabbis. Therefore, like Catholicism, one may legitimately speak of Scripture and Tradition as the twin pillars of modern Judaism. (It is not without significance that Geza Vermes titled his 1961 work on Jewish interpretation Scripture and Tradition in Judaism.)

Who Are the Rabbis?

The term “rabbi” means “one greater than I” and was an honorific way of referring to one’s teacher. As far as our current state of knowledge is concerned, the term dates back no further than the first century A.D., and the New Testament is the earliest text to use it. Most scholars believe the rabbis are the successors of the Pharisees, the most popular Jewish group of the New Testament era. The rabbinic literature never uses the term “Pharisee,” but there are several reasons for regarding them as the predecessors of the rabbis. First, ancient sources refer to figures such as Gamaliel and his son Simon as Pharisees, and both are claimed by the later rabbis (cf. Acts 5:34; Josephus3). Second, the Pharisaic movement was always carried by popular support, especially in Judea, whereas the two other main Jewish parties—the Sadducees and the Essenes—were either closely connected with the Temple (Sadducees) or were sectarian in nature (Essenes).4 Therefore, neither of the other two main Jewish sects had a major influence on the populace as a whole.

The main reason for connecting the Pharisees and the rabbis is that both groups considered their distinctive tradition authoritative.5 Jesus tends to agree with the Pharisees on most matters (e.g., Matthew 23:2-3), but criticizes their insistence on the authority of non-biblical tradition (e.g., Matthew 15:3; Mark 7:9). Since their tradition serves to exalt the authority of the Pharisees and the later rabbis, it is appropriate to discuss the concept in more detail.

The Rabbinic Tradition

By design, the rabbinic tradition was to be transmitted orally, not to be written. The earliest rabbis, whose opinions are recorded in the Mishna, are called the Tanna’im, or “repeaters” of the oral tradition. The rule of repetition, rather than writing, remained in effect until Rabbi Judah “the Prince” codified the Mishna in ca. A.D. 200, the first written source of Rabbinic Judaism. A rabbinic document known as Midrash Tanhuma6 questions why God initially speaks “all” the words of His law (Exodus 20:1), and then later commands Moses to “write” them down (Exodus 34:27). The rabbis explain that God initially wanted the entire Law to be delivered orally, but after Moses expressed the desire to write it down, God condescended as follows:7 “Give them the Scriptures in written form, but deliver the Mishna, the Aggada, and the Talmud orally.”8 This later Midrash expands on a common rabbinic theme, namely, that their teaching was to imitate God’s revelation at Sinai. They were to copy and read the written Law, and they were to memorize and repeat the oral law.9

The decision to write down the oral law was, therefore, seemingly a contradiction of the rabbis’ own policy. The rabbinic literature never works out the contradiction, but a number of modern scholars have offered suggestions.10 Perhaps it was simply a practical matter. One can imagine that the oral tradition eventually became too large to memorize, and different rabbis remembered different teachings in contradictory form. Therefore, writing was an attempt to standardize the rabbinic tradition, getting everyone “on the same page,” so to speak. It is also possible that the written form of the oral tradition was intended for private study to facilitate the rabbinic education. Modern scholars have analyzed the rhetoric of the Mishna in particular, finding that it is written to facilitate memorization. Ultimately, modern readers of the rabbinic literature are forced to live with a paradox: our only access to the oral law is in its written form.

Why Does the Oral Tradition Exist?

The rabbis’ own summary of the rabbinic tradition is found at the beginning of the Mishnaic tractate Pirke Avot: “be patient in judgment, raise up many students, and build a fence around the Law” of Moses (1:1). The most programmatic of these commandments is the last. One of the primary aims of the rabbinic experiment was to protect the written law from being violated. The oral law was always viewed as a complement, not a competitor, of the written Law of Moses. Some sources feature the oral law as a distinct set of traditions preserved independently,11 while others speak of the oral law as a set of authorized interpretations of the Mosaic Law and thus dependent on it.12 The latter presentation is the one that seems more plausible historically.

The rabbinic traditions were well-intended to keep people from violating biblical law. Inventing the notion of an oral law served two related purposes. First, it helped to define what the 613 biblical laws in the Pentateuch actually meant. For example, the Law of Moses instructs the Israelites to do no work on the Sabbath (Leviticus 23:3), but gives few examples of what types of work violate the Law (Numbers 15:32-36 is a rare exception). By contrast, the Mishna—the first written version of the oral law—records some 39 categories of work forbidden on the Sabbath, unpacking each in extreme detail. If one were to observe the teachings of the rabbis, he could rest assured that he had kept the Law.

Second, claiming that the oral law is traceable to Moses on Sinai serves to authorize the rabbis as tradents of the tradition, and thus as the most qualified interpreters of the Bible. In the marketplace of competing biblical interpretations, the claim to possess a stream of exceptional divine revelation would have helped the rabbis to assert their authority. The claim also ensured that no single rabbi possessed an authority of his own, for the rabbis studiously place themselves within an authorized tradition. The contribution of every esteemed sage lies in his ability to transmit accurately what he has received, not to add anything new.

What Is the Mishna?

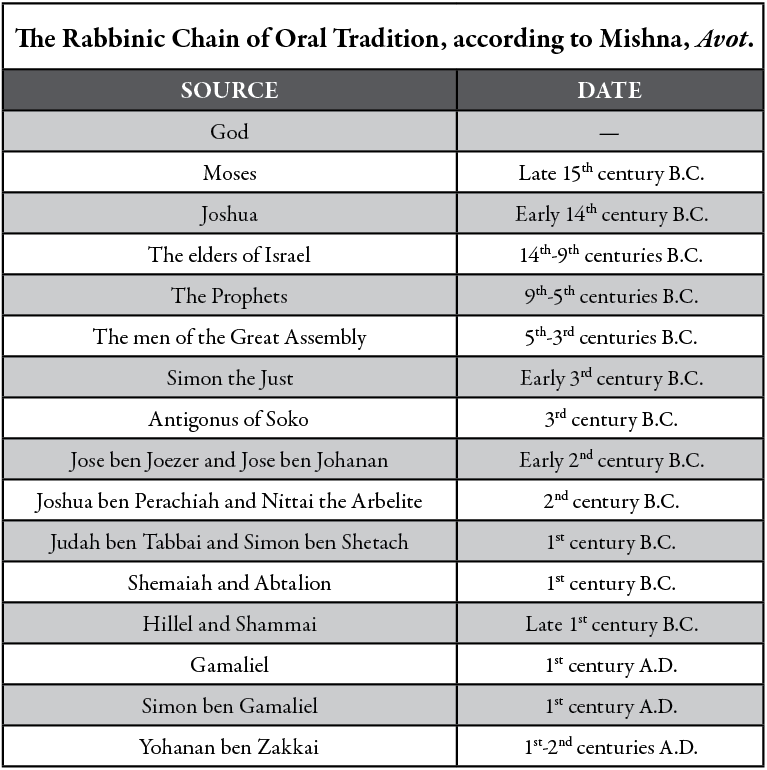

The Mishna is the first written source of Rabbinic Judaism. In this document, we have a mythical account of the origins of the Jewish oral tradition.13 We are told that, on Mount Sinai, God revealed two laws to Moses, one to be written (the Pentateuch) and the other to be passed down orally. Moses shared this oral law with Joshua, Joshua with the elders of Israel, the elders of Israel with the biblical Prophets, and the biblical Prophets with “the men of the great assembly.” From here, the oral tradition was passed on to and through various individual sages down to the time of Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai, who, following the destruction of the Temple in A.D. 70, became the founder of the movement known to us in the rabbinic literature.

The Mishna is divided into six divisions, known in English as “orders:” (1) Zeraim (“seeds”) on agriculture; (2) Moed (“festival”) on holidays; (3) Nashim (“women”) on regulations pertaining to the family; (4) Nezikin (“damages”) on cases and procedures in the Jewish court system; (5) Kodashim (“holy things”) on sacrificial procedures; and (6) Tahorot (“purities”) on ritual purity. These are the categorical groupings that encompass all of the laws governing Jewish life.

What Is the Talmud?

The Talmud, known as the Bavli, or Babylonian Talmud, is a commentary of sorts on the Mishna. The word Talmud is an Aramaic word meaning “teaching.”14 It includes much of the Mishna along with what is called the gemara, or “complete teaching.” Actually, the Talmud does not cover all of the Mishna. Only 36.5 of the Mishna’s 63 tractates, comprising only four of its six “orders,” receive comment.15 It is unclear why much of the content is omitted, but the traditional explanation is that some of the Mishna’s Palestinian agricultural concerns were irrelevant to the Babylonian context of the Talmud.

The Talmud was compiled around A.D. 500 and was an effort to impose the rabbinic rules of the land of Israel on the Babylonian Jewish community. There is another Talmud, known as the “Jerusalem Talmud,” compiled in the land of Israel about A.D. 400, but it has not been considered worthy of the same status as the Babylonian Talmud. The same is true of another collection of rabbinic tradition hailing from the land of Israel, the Tosefta (compiled ca. A.D. 300). Since traditional Jews regard the collection represented by the Babylonian Talmud to be inclusive of the earlier rabbinic tradition (at least, theoretically), when the word “Talmud” is used, it is usually only the Bavli that is intended.

The Talmud contains much material that is attributed to the rabbinic oral tradition but unrecorded in the Mishna, the Tosefta, or the Jerusalem Talmud. Two categories of content describe the non-Mishnaic material that is not necessarily paralleled in the earlier collections.16 First, we have what is called beraitot (or, in the singular, beraita’), which means “external content.” This material is “external” to the Mishna, but is nevertheless attributed to the tanna’im, or the sages of the Mishnaic period. Second, we have the teachings of the sages belonging to the generation after the Mishna. The rabbis of this era, who flourished in the third and fourth centuries A.D., are known as the ’amora’im, or “sayers.”

The Talmud is a monumental accomplishment, representing more than two million words of content and taking up an entire bookshelf in the standard editions. The Talmud is nearly five times longer than the entire Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, and is considered the authoritative expression of Jewish faith, though other rabbinic collections are also considered important for the tradition. For example, Jews traditionally treat the rabbinic commentaries, or Midrashim, with respect and mine them for encouraging material. Nevertheless, the Talmud remains the foundational text of Modern Judaism. As Talmud scholar Stephen Wald describes it,

The Talmud Bavli represents the growing literary achievement of this entire period of Jewish history—which is in fact often simply referred to as the “talmudic period.” It was ultimately accepted as the uniquely authoritative canonical work of post-biblical Jewish religion, providing the foundation for all subsequent developments in the fields of halakhah [Jewish law] and aggadah [Jewish theology]…. Despite manifest difficulties of language and content, the study of the Bavli has also achieved an unparalleled place in the popular religious culture of the Jewish people.17

Conclusion

Modern Judaism is founded on rabbinic Judaism, which most likely has its roots in the Pharisaic movement of the first centuries A.D. The rabbis’ foundational concept was the assertion that two laws were given on Sinai, one written and the other oral. The oral law was passed down from one generation of sages to the next so that the latest tradents of the tradition could be considered authoritative in their teaching. Therefore, if one accepted the oral tradition of the rabbis, one had to view with suspicion the teachings of all others. While the Pharisees apparently did not have as developed a notion of the oral tradition and its transmission, they nevertheless considered their traditions authoritative.

Eventually, the oral teachings of the rabbis were committed to writing, first in the Mishna (ca. A.D. 200), then in author writings of the so-called Tannaitic period. Finally, the Babylonian Talmud (ca. A.D. 500) became the greatest expression of authorized rabbinic teaching, incorporating the Mishna and many other traditions both from the Tannaitic and the Amoraic periods. It would be the Babylonian Talmud that Jews in the Middle Ages took as the final and fullest expression of their faith, and the text that continues to be shared with generations of Jews, both those training for the rabbinate and those seeking to grow closer to the God of the covenant. If Christians hope to reach their Jewish friends with the Gospel, it is helpful to know something about their history, tradition, and literature.18

Endnotes

1 1 Peter 3:15, ESV.

2 Jewish people refer variously to the Scriptures (the “Protestant” Christian Old Testament) as the Bible, the TaNaK (an acronym for the Law, the Prophets, and the Writings—the Torah, the Nevi’im, and the Kethuvim), or Mikra (“what is written”).

3 Flavius Josephus (1987 reprint), The Life of Flavius Josephus in The Works of Josephus, trans. William Whiston (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson), 190-196.

4 On the Pharisees, Sadducees, and Essenes as the three main Jewish groups, along with their characteristic teachings, see Josephus, Jewish War, 2:119-166; Antiquities, 13:171-173.

5 For the Pharisees, e.g., Mark 7:1-13; Josephus, Antiquities 13:297, 408; for the rabbis, e.g., Mishna, Avot 1-2.

6 Published by Solomon Buber.

7 All translations of ancient languages are mine unless otherwise noted.

8 Ki Tisa 17.

9 Cf. Jerusalem Talmud, Megilla 4:1.

10 See Elizabeth Shanks Alexander (2007), “The Orality of Rabbinic Writing,” The Cambridge Companion to the Talmud and Rabbinic Literature, eds. Charlotte Elisheva Fonrobert and Martin S. Jaffee (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 38-57.

11 E.g., Babylonian Talmud, Eruvin 54b.

12 E.g., Babylonian Talmud, Menahot 29b.

13 Avot 1-2.

14 The Mishna is written in Hebrew, but the Babylonian Talmud (when it does not quote the Mishna) is written in Aramaic. Therefore, the rabbis who compiled the Talmud were bilingual.

15 The Talmud excludes all of Zeraim with the exception of the tractate Berakot and all of Tahorot with the exception of the tractate Niddah.

16 On the complex relationship between the Babylonian Talmud and earlier rabbinic material, see H.L. Strack and Günter Stemberger (1992), Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash, trans. and ed. Markus Bockmuehl (Philadelphia, PA: Fortress), pp. 197-201.

17 Stephen Wald (2007), “Talmud, Bavli,” in The Encyclopedia Judaica, ed. Fred Skolnik and Michael Berenbaum (San Francisco/Jerusalem: MacMillan/Keter), second edition, 19:470.

18 To learn more, the Sefaria website and mobile application are excellent (sefaria.org).

The post What Is Rabbinic Judaism? appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>The post What is Messianic Judaism? appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>[EDITOR’S NOTE: AP auxiliary writer Dr. Rogers is the Director of the Graduate school of Theology and Associate Professor of Bible at Freed-Hardeman University. He holds an M.A. in New Testament from Freed-Hardeman University as well as an M.Phil. and Ph.D. in Hebraic, Judaic, and Cognate Studies from Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion.]

“They wish to be both Jews and Christians, but are neither Jews nor Christians.” This is how the church father Jerome (ca. A.D. 345-430) characterized the “Nazareans,” one of the early Jewish-Christian groups that observed the Law of Moses while claiming faith in Jesus.1 The writings of the church fathers, in fact, regularly featured comments about early Christian sects who continued to observe the Mosaic Law. The existence of these groups should not surprise us since the New Testament already contests those who seek to impose the Mosaic Law on Christians. For example, Paul writes to the Galatians, “You are severed from Christ, you who would be justified by the law; you have fallen away from grace” (Galatians 5:4, ESV).

The tendency of some Christians to adopt the Mosaic Law, in part or in totality, has not faded with the passage of time. A modern movement, known as Messianic Judaism, seeks to return to these ancient ways. Although there is great variety in the beliefs and practices of Messianic Jews, this article shall attempt an overview of at least the key tenets of this movement.

The Attraction of Messianic Judaism

Messianic Judaism has attracted a great deal of attention in recent years. The reasons for its appeal are many. First, the atrocities of the Holocaust made the Western world in general more sympathetic to Jews and Judaism. This is exemplified by the Nostra Aetate declaration of Pope Paul VI which erases some of the most censorious anti-Semitic statements in Catholic tradition.2 Second, the appeal of Messianic Judaism is its seeming authenticity. Jesus was a Jew and lived a perfect life under the Law of Moses (Galatians 4:4).3 If we are to be like Jesus, does it not stand to reason that we too should live as He did? Would this not mean accepting the Law of Moses, adopting Jewish customs and beliefs, and speaking as He spoke?

Third, the New Testament reveals that the earliest Christians were Jewish and lived in accord with the Mosaic Law. James refers to the church as a “synagogue” (James 2:2, ASV), and it is clear that the observance of circumcision and Levitical dietary restrictions presented no problem until Peter’s vision (Acts 10:9-16). Even after the admission of the Gentiles into the church certain Jewish restrictions were still imposed (Acts 15:19-21). Fourth, Messianic Judaism is appealing because it is different. People are always interested in something new (Acts 17:21), and the novelty factor of Messianic Judaism is significant to most Christians. To some it is attractive to speak of Yeshua‘ hammeshîach (“Jesus the Messiah”) rather than “Jesus Christ”; of habberîth hachadāshāh rather than the “new covenant”; of their “rabbi” rather than their “minister.”

Fifth, Messianic Judaism is appealing because it is similar to Christianity. Most of the converts to Messianic Judaism are not Jews but Christians. Therefore, it is in the best interest of Messianic Jewish congregations to stress their similarities with mainline or evangelical Christianity. As a result, those who “convert” to Messianic Judaism do not feel as though they are abandoning one religion for another. Sixth, the premillennialist strand of evangelical Christianity insists the Jews continue to be God’s chosen people. They believe Jesus will someday establish an earthly kingdom based in Jerusalem, leading them to advocate Zionism (the political position that the state of Israel belongs exclusively to the Jewish people), which aligns their political beliefs with those of many North American Jews.

Seventh, many Protestant denominations embrace or even promote Messianic Judaism. One newsworthy example was the Avodath Yisrael congregation in suburban Philadelphia which was partially funded by the Presbyterian church of America.4 Messianic Judaism is designed in many places, then, to look simply like a more ancient and authentic Christianity. Many Christians feel they can turn to Messianic Judaism, sacrificing nothing while gaining a more genuine and biblical form of faith.

What Messianic Jews Believe

To summarize the beliefs of any religious group is a dangerous proposition. Imagine if someone were asked, “What do Christians believe?” The answers are not easy to give. Christians are incredibly diverse in what they believe and teach. While most of us recognize the problematic nature of diversity among our own religious groups, we do not apply the same perception to other faiths. For example, Christians in mostly monoreligious contexts (such as the American South) tend to think all Jews and Muslims believe and practice the same things. They do not. Attempting to characterize any movement in monolithic terms is unfair.

So we must admit that, when we study the Messianic Jewish movement, we find great diversity of belief and practice. Some Messianic Jews, for example, are unapologetically Christian, while some insist on being Jewish followers of Jesus, rejecting the “Christian” label. Some conduct worship services that feature Hebrew liturgies, while others toss in a few Hebrew terms (e.g., “rabbi,” “Yeshua”). Some accept the authority of rabbinic Jewish tradition, while others believe their authority ends with the New Testament. In other words, all Messianic Jews blend Jewish and Christian terms, traditions, and teachings, but the ratio of these elements differs greatly from one congregation to another. Nevertheless, we shall attempt to paint in broad strokes, and if the reader’s local version of Messianic Judaism happens to be different, perhaps we can be forgiven.

While some forms of Christianity have opened toward Jews and Judaism since the Holocaust, even viewing the two religions as compatible, Judaism itself has been more reluctant to sacrifice its distinctiveness. It is true that liberal strands of Judaism, such as the Reform movement, have been more open to the inclusion of Messianic Judaism than other Jewish groups,5 but no Jewish denomination has so far extended “the right hand of fellowship” to Messianic Jews. Shapiro states, “all four major denominations [Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, and Reconstructionist] agree that Messianic Jews are not acceptably Jewish, and that Jewishness is utterly incompatible with belief in the divinity of Jesus Christ.”6

This brings us to the first significant difference between Messianic Judaism and Christianity. Messianic Jews not only affirm Jesus as the Messiah, but also believe He is the Son of God. One of the oldest creedal assertions of Judaism is the Shema, which states the fundamental principle that “God is one” (Deuteronomy 6:4). Although Christians do not view the passage as contradicting the notion of “God-in-three-persons,” Jews have always used the passage to defend absolute monotheism, ruling out the divinity of Jesus. Jews generally acknowledge that Jesus was a great prophet, but definitely not the Son of God. To admit otherwise is to deny one of the fundamental confessions of Jewish faith.

Another major difference is that Messianic Jews believe the Messiah has come in the form of Jesus of Nazareth whereas traditional Jews believe the Messiah is yet to come. A seat is still reserved at the traditional Passover celebration for Elijah, who is to herald the coming of the Messiah (Malachi 4:5). Jews take seriously that the “age to come” is still future. A third difference is the authority of the New Testament. While Jews will admit Jesus into the ranks of Jewish prophets or traditional sages, they will not extend the same privilege to the apostles. They generally believe, along with much of New Testament scholarship, that Paul in particular corrupted the religion of Jesus, creating a hybrid faith that was eventually responsible for extracting the Jewish elements from Christianity. Messianic Jews, by contrast, continue to follow the teachings of the apostles.

Conclusion

David Stern, one of the primary voices within the tradition, insists that Messianic Jews are both fully Jewish and fully Christian.7 This might be possible if all the word “Jew” refers to is an ethnic identity. But the majority of Messianic Jews in the United States are not ethnically Jewish. That means these non-Jewish members of Messianic Judaism must believe they are Jewish in another way. As Ariel puts it,

Ironically, while advocating mostly conservative views on political, social, and cultural issues, this evangelical-Jewish movement is an avant-garde form of post-modern realities, in which individuals and communities exercise their freedom to carry a series of identities and struggle to negotiate between them. Such hybrids have become prevalent in contemporary Christian and Jewish communities, which, since the 1960s, often tended toward innovation and amalgamation of different traditions and practices.8

Messianic Judaism seeks a path between two faiths that have been historically opposed to one another. This is commendable in principle. Christians and Jews should engage in meaningful dialogue to learn from one another and to avoid many of the atrocities of the past.

That said, Messianic Judaism suffers from the same mistake that the ancient Christian-Jewish heresies committed. By seeking to be both Jews and Christians, they end up being neither. It is instructive that, although the four modern divisions of Judaism disagree on exactly what constitutes Jewishness, they seem united in the belief that Messianic Jews are not authentically Jewish. It is mostly the Christian world that has created and sustained Messianic Judaism, and the greatest growth has come primarily from the evangelical Christian population.

Paul understood Christ to be the “end” of the Law (Romans 10:4), and Christianity to erase the distinctions between “Jew” and “Greek” (Galatians 3:28). The author of Hebrews understood the “new covenant” to mark a different era under which the Mosaic covenant would be obsolete (Hebrews 8:7-13). For Christians who accept the authority of the New Testament, these statements leave little room for Judaism. Christianity is the great equalizer, but all must turn to Christ, for “there is salvation in no one else” (Acts 4:12). Judaism cannot accept the Messianic Jewish movement as an authentic expression of Judaism, and it seems the apostles could not accept the movement as an authentic version of Christianity. So what is Messianic Judaism?

Endnotes

1 Jerome, Epistle 112.13 (translation mine).

2 http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_decl_19651028_nostra-aetate_en.html.

3 The title of Geza Vermes’ 1973 monograph, Jesus the Jew, hardly raises an eyebrow today, but was quite controversial in its time. The book, among other works of New Testament scholarship, provoked the so-called “third quest of the historical Jesus,” a movement to situate Jesus properly within his first-century Jewish context. It is no accident that Messianic Judaism was born anew in the 1970s. See Geza Vermes (1973), Jesus the Jew: A Historian’s Reading of the Gospels (London: Collins).

4 Jason Byassee (2005), “Can a Jew be a Christian? The Challenge of Messianic Judaism,” Christian Century, 3:22-27, May.

5 E.g., Dan Cohn-Sherbock, and Fran Samuelson (2007), Messianic Jews (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

6 Faydra Shapiro (2012), “Jews for Jesus: The Unique Problem of Messianic Judaism,” Journal of Religion and Society, 14:2.

7 David Stern (1988), Messianic Jewish Manifesto (Jerusalem/Gaithersburg, MD: Jewish New Testament Publications), p. 4.

8 Yaakov Ariel (2012), “A Different Kind of Dialogue? Messianic Judaism and Jewish-Christian Relations,” CrossCurrents, 62:326.

The post What is Messianic Judaism? appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>The post Controversial Orthodox Jews Call for Renewal of Sacrifices appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>Some Jews are against restoring animal sacrifices. Doniel Hartman, of the Shalom Institute in Jerusalem, said of the A.D. 70 destruction: “Around that time, animal sacrifice, as a mode of religious worship, stopped…. Moving back in that direction is not progress” (quoted in “Extremist…”). Muslims also are protesting the move to renew animal sacrifices. Jerusalem’s senior Islamic cleric, Mohommed Hussein, said: “Regrettably, there are many extremist Israeli groups who want to carry out their plans…. Let them say what they want, Al Aqsa [formerly the site of Herod’s temple—CC] is a Muslim mosque” (quoted in “Extremist…”). Jewish leaders have conceded that the sacrifices will not be renewed anytime soon.

The Sanhedrin was “[t]he Jewish court in Jerusalem from the Persian through the Roman period; it had both religious and political powers and comprised the elite (both priestly and lay) of society” (Moulder, 1988, p. 331, parenthetical in orig.). Though the Sanhedrin was a manmade institution, absent any divine mandate, these modern Jews are reviving it to add perceived authority and significance to their movement.

Of course, the Bible plainly teaches that the Old Covenant between God and Israel was removed and replaced when Christ provided the single, perfect sacrifice for the sins of humanity. Consider these biblical passages:

For if that first covenant had been faultless, then no place would have been sought for a second. Because finding fault with them, He says: “Behold, the days are coming, says the Lord, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah—not according to the covenant that I made with their fathers in the day when I took them by the hand to lead them out of the land of Egypt…” (Hebrews 8:7-9; cf. Jeremiah 31:31-34).

But now we have been delivered from the law, having died to what we were held by, so that we should serve in the newness of the Spirit and not in the oldness of the letter (Romans 7:6).

[H]aving wiped out the handwriting of requirements that was against us, which was contrary to us. And He has taken it out of the way, having nailed it to the cross (Colossians 2:14; cf. 2 Corinthians 3:2-11).

For He Himself is our peace, who has made both one, and has broken down the middle wall of separation, having abolished in His flesh the enmity, that is, the law of commandments contained in ordinances, so as to create in Himself one new man from the two, thus making peace… (Ephesians 2:14-15; cf. Galatians 4:21-31).

The prophets foretold the coming of a new covenant, and the Lord established it in the New Testament age; the theme of the entire Bible centers around God’s plan to redeem mankind through His Son and the church that Christ would establish. So, persisting in the Jewish faith in the Christian age is out of harmony with both Old and New Testaments.

However, consistency demands that modern Jews keep Old Testament sacrificial policy. As it stands now, the only religious rite on which all Jews seem to agree is the observation of the Sabbath (Korobkin, 2004; Ridenour, 2001, p. 68). While the Bible makes it plain that Christians must not observe the Sabbath as a holy day (Colossians 2:16; see Wright, 1977), it seems unthinkable that any religionists would adhere to one portion of Mosaic legislation and dismiss hundreds of other regulations as being non-binding for those alive today. The Seventh-Day Adventists are eager to develop this dichotomy, but the Bible makes no such distinction (“Fundamental Beliefs,” 2007; see Lyons, 2001).

Non-orthodox Jews have attempted to justify their piecemeal application of the Old Covenant by arguing that that God “has no delight in sacrifices, and that the sacrifice He has chosen is a contrite spirit” (e.g., Morris, 1984, 7[1]:170; see Psalms 34:18; 51:17; etc.). While the Bible certainly teaches that the follower of God must be contrite, he also must keep God’s commandments. To teach otherwise is to ignore multiple Old Testament passages that reflect how God insisted that Israel keep every statute of the Covenant.

But if you do not obey Me, and do not observe all these commandments, and if you despise my statutes, or if your soul abhors My judgments, so that you do not perform all My commandments, but break my covenant, I also will do this to you: I will even appoint terror over you, wasting disease and fever which shall consume the eyes and cause sorrow of heart…. I will set My face against you, and you shall be defeated by your enemies…. And after all this, if you do not obey Me, then I will punish you seven times more for your sins (Leviticus 26:14-18, emp. added; cf. 19:37; Deuteronomy 5:29; etc.).

And you shall have a tassel, that you may look upon it and remember all the commandments of the Lord and do them, and that you may not follow the harlotry to which your own heart and your own eyes are inclined, and that you may remember and do all My commandments, and be holy for your God (Numbers 15:39-40, emp. added).

We could list many similar passages from the Mosaic law. We may never understand fully why some Jews are trying to revive sacrificial practices, or for that matter, any portion of the Old Testament. Perhaps is it largely because of what Ahlstrom noted: “In addition to these domestic confrontations, secularization, increased social mobility, and the decline of anti-Semitism tended to erode the Jewish sense of particularity” (1973, p. 984). It could be that modern Jews feel a need to authenticate, bolster, and/or justify their religion by restoring ancient practices, starting with animal sacrifices and ultimately, logically culminating in a rebuilt temple (see “Extremist…”).

Because modern Jewish faith is based squarely on a rejection of the best-attested historical fact in antiquity, the resurrection of Jesus Christ, one might expect the Jewish religion to exhibit striking confusion and contradiction (see Butt and Lyons, 2006, pp. 135-168). Those of us at Apologetics Press will continue to stress that the evidence proves that “we have found the Messiah,” the only Son of God, Jesus Christ (John 1:41; see Butt, 2002). Man gains access to the Father only through His Son, Jesus Christ (John 14:6-7).

REFERENCES

Ahlstrom, Sydney E. (1973), A Religious History of the American People (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press).

Butt, Kyle (2002), “What Did You Expect?,” [On-line], URL: http://apologeticspress.org/articles/1780.

Butt, Kyle and Eric Lyons (2006), Behold! The Lamb of God (Montgomery, AL: Apologetics Press).

“Extremist Rabbis Call for Return of Animal Sacrifice” (2007), The Associated Press, [On-line], URL: http://www.cnn.com/2007/WORLD/meast/02/28/israel.animal.ap/index.html.

“Fundamental Beliefs” (2007), Seventh-Day Adventist Church, [On-line], URL: http://www.adventist.org/beliefs/fundamental/index.html.

Korobkin, Daniel N. (2004), “Lost in Translation: Parshat Beher-Bechukotai (Leviticus 25:1-27:34),” [On-line], URL: http://www.jewishjournal.com/home/searchview.php?id=12238.

Lyons, Eric (2001), “Which Law Was Abolished?,” [On-line], URL: http://apologeticspress.org/articles/1659.

Morris, Joseph (1894), “Note by the Author of ‘The Ideal in Judaism’,” The Jewish Quarterly Review, 7[1]:169-172, October.

Moulder, W. J. (1988), “Sanhedrin,” International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, ed. Geoffrey W. Bromiley (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans).

Ridenour, Fritz (2001), So What’s the Difference? (Ventura, CA: Regal).

Wright, Gerald N. (1977), Sabbatarian: Concordance and Commentary (Fort Worth, TX: Star Bible Publications).

The post Controversial Orthodox Jews Call for Renewal of Sacrifices appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>The post Antisemitism and the Crucifixion of Christ: Who Murdered Jesus? appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>The stir over the film stems from the role of the Jews in their involvement in Christ’s crucifixion. In fact, outcries of “anti-Semitism” have been vociferous, especially from representatives of the Anti-Defamation League. Their contention is that Jews are depicted in the film as “bloodthirsty, sadistic, money-hungry enemies of God” who are portrayed as “the ones responsible for the decision to crucify Jesus” (as quoted in Hudson, 2003; cf. Zoll, 2003). The fear is that the film will fuel hatred and bigotry against Jews. A committee of nine Jewish and Catholic scholars unanimously found the film to project a uniformly negative picture of Jews (“ADL and Mel…”). The Vatican has avoided offering an endorsement of the film by declining to make an official statement for the time being (“Vatican Has Not…”; cf. “Mel Gibson’s…”). This action is to be expected in view of the conciliatory tone manifested by Vatican II (Abbott, 1955, pp. 663-667). Even Twentieth Century Fox has decided not to participate in the distribution of the film (“20th Decides…”; cf. “Legislator Tries…”; O’Reilly…”).

Separate from the controversy generated by Gibson’s film, the more central issue concerns to what extent the Jewish generation of the first century contributed to, or participated in, the death of Christ. If the New Testament is the verbally inspired Word of God, then it is an accurate and reliable report of the facts, and its depiction of the details surrounding the crucifixion are normative and final. That being the case, how does the New Testament represent the role of the Jews in the death of Christ?

A great many verses allude to the role played by the Jews, especially the leadership, in the death of Jesus. For some time prior to the crucifixion, the Jewish authorities were determined to oppose Jesus. This persecution was aimed at achieving His death:

So all those in the synagogue, when they heard these things, were filled with wrath, and rose up and thrust Him out of the city; and they led Him to the brow of the hill on which their city was built, that they might throw Him down over the cliff (Luke 4:28-30, emp. added).

Therefore the Jews sought all the more to kill Him, because He not only broke the Sabbath, but also said that God was His Father, making Himself equal with God (John 5:18-19, emp. added).

After these things Jesus walked in Galilee; for He did not want to walk in Judea, because the Jews sought to kill Him… “Did not Moses give you the law, yet none of you keeps the law? Why do you seek to kill Me?” (John 7:1-2,19, emp. added).

“I know that you are Abraham’s descendants, but you seek to kill Me, because My word has no place in you. I speak what I have seen with My Father, and you do what you have seen with your father.” They answered and said to Him, “Abraham is our father.” Jesus said to them, “If you were Abraham’s children, you would do the works of Abraham. But now you seek to kill Me, a Man who has told you the truth which I heard from God. Abraham did not do this.” Then they took up stones to throw at Him; but Jesus hid Himself and went out of the temple, going through the midst of them, and so passed by (John 8:37-41,59, emp. added).

Then the Jews took up stones again to stone Him…. Therefore they sought again to seize Him, but He escaped out of their hand (John 10:31-32,39, emp. added).

Then, from that day on, they plotted to put Him to death…. Now both the chief priests and the Pharisees had given a command, that if anyone knew where He was, he should report it, that they might seize Him (John 11:53, 57, emp. added).

And He was teaching daily in the temple. But the chief priests, the scribes, and the leaders of the people sought to destroy Him, and were unable to do anything; for all the people were very attentive to hear Him (Luke 19:47-48, emp. added).

And the chief priests and the scribes sought how they might kill Him, for they feared the people (Luke 22:2, emp. added).

Then the chief priests, the scribes, and the elders of the people assembled at the palace of the high priest, who was called Caiaphas, and plotted to take Jesus by trickery and kill Him (Matthew 26:3-4, emp. added).

These (and many other) verses demonstrate unquestionable participation of the Jews in bringing about the death of Jesus. One still can hear the mournful tones of Jesus Himself, in His sadness over the Jews rejecting Him: “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the one who kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to her! How often I wanted to gather your children together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings, but you were not willing! See! Your house is left to you desolate” (Matthew 23:37-39). He was referring to the destruction of Jerusalem and the demise of the Jewish commonwealth at the hands of the Romans in A.D. 70. Read carefully His unmistakable allusion to the reason for this holocaustic event:

Now as He drew near, He saw the city and wept over it, saying, “If you had known, even you, especially in this your day, the things that make for your peace! But now they are hidden from your eyes. For days will come upon you when your enemies will build an embankment around you, surround you and close you in on every side, and level you, and your children within you, to the ground; and they will not leave in you one stone upon another, because you did not know the time of your visitation” (Luke 19:41-44).

He clearly attributed their national demise to their stubborn rejection of Him as the predicted Messiah, Savior, and King.

Does the Bible, then, indicate that a large percentage, perhaps even a majority, of the Jews of first century Palestine was “collectively guilty” for the death of Jesus? The inspired evidence suggests so. Listen carefully to the apostle Paul’s assessment, keeping in mind that he, himself, was a Jew—in fact, “a Hebrew of the Hebrews” (Philippians 3:5; cf. Acts 22:3; Romans 11:1; 2 Corinthians 11:22). Speaking to Thessalonian Christians, he wrote:

For you, brethren, became imitators of the churches of God which are in Judea in Christ Jesus. For you also suffered the same things from your own countrymen, just as they did from the Judeans, who killed both the Lord Jesus and their own prophets, and have persecuted us; and they do not please God and are contrary to all men, forbidding us to speak to the Gentiles that they may be saved, so as always to fill up the measure of their sins; but wrath has come upon them to the uttermost (1 Thessalonians 2:14-16, emp. added).

This same apostle Paul met with constant resistance from fellow Jews. After he spoke at the Jewish synagogue in Antioch of Pisidia, a crowd of people that consisted of nearly the whole city gathered to hear him expound the Word of God. Notice the reaction of the Jews in the crowd:

But when the Jews saw the multitudes, they were filled with envy; and contradicting and blaspheming, they opposed the things spoken by Paul. Then Paul and Barnabas grew bold and said, “It was necessary that the word of God should be spoken to you first; but since you reject it, and judge yourselves unworthy of everlasting life, behold, we turn to the Gentiles….” But the Jews stirred up the devout and prominent women and the chief men of the city, raised up persecution against Paul and Barnabas, and expelled them from their region (Acts 13:45-46,50-51).

Paul met with the same resistance from the general Jewish public that Jesus encountered—so much so that he wrote to Gentiles concerning Jews: “Concerning the gospel they are enemies for your sake” (Romans 11:28). He meant that the majority of the Jews had rejected Christ and Christianity. Only a “remnant” (Romans 11:5), i.e., a small minority, embraced Christ.

What role did the Romans play in the death of Christ? It certainly is true that Jesus was crucified on a Roman cross. First-century Palestine was under the jurisdiction of Rome. Though Rome permitted the Jews to retain a king in Judea (Herod), the Jews were subject to Roman law in legal matters. In order to achieve the execution of Jesus, the Jews had to appeal to the Roman authorities for permission (John 18:31). A simple reading of the verses that pertain to Jewish attempts to acquire this permission for the execution are clear in their depiction of Roman reluctance in the matter. Pilate, the governing procurator in Jerusalem, sought literally to quell and diffuse the Jewish efforts to kill Jesus. He called together the chief priests, the rulers, and the people and stated plainly to them:

“You have brought this Man to me, as one who misleads the people. And indeed, having examined Him in your presence, I have found no fault in this Man concerning those things of which you accuse Him; no, neither did Herod, for I sent you back to him; and indeed nothing deserving of death has been done by Him. I will therefore chastise Him and release Him” (for it was necessary for him to release one to them at the feast). And they all cried out at once, saying, “Away with this Man, and release to us Barabbas”—who had been thrown into prison for a certain rebellion made in the city, and for murder. Pilate, therefore, wishing to release Jesus, again called out to them. But they shouted, saying, “Crucify Him, crucify Him!” Then he said to them the third time, “Why, what evil has He done? I have found no reason for death in Him. I will therefore chastise Him and let Him go.” But they were insistent, demanding with loud voices that He be crucified. And the voices of these men and of the chief priests prevailed. So Pilate gave sentence that it should be as they requested. And he released to them the one they requested, who for rebellion and murder had been thrown into prison; but he delivered Jesus to their will (Luke 23:14-25).

It is difficult to conceptualize the level of hostility possessed by the Jewish hierarchy, and even by a segment of the Jewish population, toward a man who had done nothing worthy of such hatred. It is incredible to think that they would clamor for the release of a known murderer and insurrectionist, rather than allow the release of Jesus. Yes, the Roman authority was complicit in the death of Jesus. But Pilate would have had no interest in pursuing the matter if the Jewish leaders and crowd had not pressed for it. In fact, he went to great lengths to perform a symbolic ceremony in order to communicate the fact that he was not responsible for Jesus’ death. He announced to the multitude: “I am innocent of the blood of this just Person. You see to it” (Matthew 27:24). Technically, the Romans cannot rightly be said to be ultimately responsible. If the Jews had not pressed the matter, Pilate never would have conceded to having Him executed. The apostle Peter made this point very clear by placing the blame for the crucifixion of Jesus squarely on the shoulders of Jerusalem Jews:

Men of Israel…the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the God of our fathers, glorified His Servant Jesus, whom you delivered up and denied in the presence of Pilate, when he was determined to let Him go. But you denied the Holy One and the Just, and asked for a murderer to be granted to you, and killed the Prince of life, whom God raised from the dead, of which we are witnesses (Acts 3:12-16, emp. added).

Notice that even though the Romans administered the actual crucifixion, Peter pointedly stated to his Jewish audience, not only that Pilate wanted to release Jesus, but that the Jews (“you”)—not the Romans—“killed the Prince of life.”

Does God lay the blame for the death of Christ on the Jews as an ethnic group? Of course not. Though the generation of Jews who were contemporary to Jesus cried out to Pilate, “His blood be on us and on our children” (Matthew 27:25, emp. added), it remains a biblical fact that “the son shall not bear the guilt of the father” (Ezekiel 18:20). A majority of a particular ethnic group in a particular geographical locale at a particular moment in history may band together and act in concert to perpetrate a social injustice. But such an action does not indict all individuals everywhere who share that ethnicity. “For there is no partiality with God” (Romans 2:11), and neither should there be with any of us.

In fact, the New Testament teaches that ethnicity should have nothing to do with the practice of the Christian religion—which includes how we see ourselves, as well as how we treat others. Listen carefully to Paul’s declarations on the subject: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus. And if you are Christ’s, then you are Abraham’s seed” (Galatians 3:28-29, emp. added). Jesus obliterates the ethnic distinction between Jew and non-Jew:

For He Himself is our peace, who has made both one, and has broken down the middle wall of separation, having abolished in His flesh the enmity, that is, the law of commandments contained in ordinances, so as to create in Himself one new man from the two, thus making peace, and that He might reconcile them both to God in one body through the cross, thereby putting to death the enmity (Ephesians 2:14-17).

In the higher sense, neither the Jews nor the Romans crucified Jesus. Oh, they were all complicit, including Judas Iscariot. But so were we. Every accountable human being who has ever lived or ever will live has committed sin that necessitated the death of Christ—if atonement was to be made so that sin could be forgiven. Since Jesus died for the sins of the whole world (John 3:16; 1 John 2:2), every sinner is responsible for His death. But that being said, the Bible is equally clear that in reality, Jesus laid down His own life for humanity: “I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd gives His life for the sheep…. Therefore My Father loves Me, because I lay down My life that I may take it again. No one takes it from Me, but I lay it down of Myself. I have power to lay it down, and I have power to take it again” (John 10:11,17-18; cf. Galatians 1:4; 2:20; Ephesians 5:2; 1 John 3:16). Of course, the fact that Jesus was willing to sacrifice Himself on the behalf of humanity does not alter the fact that it still required human beings, in this case first-century Jews, exercising their own free will to kill Him. A good summary passage on this matter is Acts 4:27-28—“for of a truth in this city against thy holy Servant Jesus, whom thou didst anoint, both Herod and Pontius Pilate, with the Gentiles and the peoples of Israel, were gathered together, to do whatsoever thy hand and thy council foreordained to come to pass.”

CONCLUSION

Anti-Semitism is sinful and unchristian. Those who crucified Jesus are to be pitied. Even Jesus said concerning them: “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they do” (Luke 23:34). But we need not deny or rewrite history in the process. We are now living in a post-Christian culture. If Gibson would have produced a movie depicting Jesus as a homosexual, the liberal, “politically correct,” anti-Christian forces would have been the first to defend the undertaking under the guise of “artistic license,” “free speech,” and “creativity.” But dare to venture into spiritual reality by showing the historicity of sinful man mistreating the Son of God, and the champions of moral degradation and hedonism raise angry, bitter voices of protest. The irony of the ages is—He died even for them.

REFERENCES

Abbott, Walter, ed. (1966), The Documents of Vatican II (New York, NY: America Press).

“ADL and Mel Gibson’s ‘The Passion,’ ” [On-line], URL: http://www.adl.org/interfaith/gibson_qa.asp.

Hudson, Deal (2003), “The Gospel according to Braveheart,” The Spectator, [On-line], URL: http://www.spectator.co.uk/article.php3?table=old§ion=current&issue=2003-09-20&id=3427&searchText=.

“Legislator Tries to Censor Mel Gibson’s ‘The Passion,’ ” [On-line], URL: http://www.newsmax.com/archives/ic/2003/8/27/124709.shtml.

“Mel Gibson’s ‘Passion’ Makes Waves,” [On-line], URL: http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2003/08/08/entertainment/main567445.shtml.

Novak, Michael (2003), “Passion Play,” The Weekly Standard, [On-line], URL: http://www.weeklystandard.com/Content/Public/Articles/000/000/003/014ziqma.asp.

“O’Reilly: Elite Media out to Destroy Mel Gibson,” [On-line], URL: http://www.newsmax.com/archives/ic/2003/9/15/223513.shtml.

Passion website, [On-line], URL: http://www.passion-movie.com/english/index.html.

“20th Decides Against Distributing Gibson’s ‘The Passion,’ ” [On-line], URL: http://www.imdb.com/SB?20030829#3.

“Vatican Has Not Taken A Position on Gibson’s Film ‘The Passion,’ Top Cardinal Assures ADL,” [On-line], URL: http://www.adl.org/PresRele/VaticanJewish_96/4355_96.htm.

Zoll, Rachel (2003), “Jewish Civil Rights Leader Says Actor Mel Gibson Espouses Anti-Semitic Views,” [On-line], URL: http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/news/archive/2003/09/19/national1505EDT0626.DTL.

The post Antisemitism and the Crucifixion of Christ: Who Murdered Jesus? appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>