The post Has the Bible Been Corrupted?—What the Scholars Say appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>F.F. Bruce (1910-1990)

- Greek Professor: University of Edinburgh and the University of Leeds

- Chaired Department of Biblical History and Literature at the University of Sheffield

- Honorary Doctor of Divinity from Aberdeen University

- Rylands Professor of Biblical Criticism & Exegesis at the University of Manchester

- Authored over 40 books

- Editor of both The Evangelical Quarterly and the Palestine Exploration Quarterly

“The variant readings about which any doubt remains among textual critics of the N.T. affect no material question of historic fact or of Christian faith and practice.”1

“In view of the inevitable accumulation of such errors over so many centuries, it may be thought that the original texts of the New Testament documents have been corrupted beyond restoration. Some writers, indeed, insist on the likelihood of this to such a degree that one sometimes suspects they would be glad if it were so. But they are mistaken. There is no body of ancient literature in the world which enjoys such a wealth of good textual attestation as the New Testament.”2

“Something more ought to be said, and said with emphasis. We have been discussing various textual types, and reviewing their comparative claims to be regarded as best representatives of the original New Testament. But there are not wide divergencies between these types, of a kind that could make any difference to the Church’s responsibility to be a witness and guardian of Holy Writ.”3

“If the variant readings are so numerous, it is because the witnesses are so numerous. But all the witnesses, and all the types which they represent, agree on every article of Christian belief and practice.”4

“If the very number of manuscripts increases the total of scribal corruptions, it supplies at the same time the means of checking them.”5

Bruce Metzger (1914-2007)

- Scholar of Greek and NT Textual Criticism

- Late Professor at Princeton Theological Seminary (46 years)

- Recognized authority on the Greek text of the New Testament

- Served on the board of the American Bible Society

- Driving force of the United Bible Societies’ series of Greek Texts

- Chairperson of the NRSV Bible Committee

- Widely considered one of the most influential New Testament scholars of the 20th century

“[E]ven if we had no Greek manuscripts today, by piecing together the information from these translations from a relatively early date, we could actually reproduce the contents of the New Testament. In addition to that, even if we lost all the Greek manuscripts and the early translations, we could still reproduce the contents of the New Testament from the multiplicity of quotations in commentaries, sermons, letters, and so forth of the early church fathers.”6

Brooke Foss Westcott (1825-1901)

- Biblical scholar, theologian, textual critic

- Bishop of Durham

- Held the Regius Professorship of Divinity at Cambridge

- Co-edited The New Testament in the Original Greek

Fenton John Anthony Hort (1828-1892)

- Textual critic

- Irish theologian

- Professor at Cambridge

- Co-edited The New Testament in the Original Greek

“With regard to the great bulk of the words of the New Testament…there is no variation or other ground of doubt.”7

“[T]he amount of what can in any sense be called substantial variation is but a small fraction of the whole residuary variation, and can hardly form more than a thousandth part of the entire text.”8

“Since there is reason to suspect that an exaggerated impression prevails as to the extent of possible textual corruption in the New Testament…we desire to make it clearly understood beforehand how much of the New Testament stands in no need of a textual critic’s labours.”9

“[I]n the variety and fullness of the evidence on which it rests the text of the New Testament stands absolutely and unapproachably alone among ancient prose writing.”10

“The books of the New Testament as preserved in extant documents assuredly speak to us in every important respect in language identical with that in which they spoke to those for whom they were originally written.”11

“[T]he words in our opinion still subject to doubt can hardly amount to more than a thousandth part of the whole New Testament.”12

J.W. McGarvey (1829-1911)

- Minister, author, educator

- Taught 46 years in the College of the Bible in Lexington, Kentucky

- Served as President from 1895 to 1911

“All the authority and value possessed by these books when they were first written belong to them still.”13

Benjamin Warfield (1852-1921)

- Professor of Theology at Princeton Seminary (1887 to 1921)

- Last of the great Princeton theologians

“[S]uch has been the providence of God in preserving for His Church in each and every age a competently exact text of the Scriptures, that not only is the New Testament unrivalled among ancient writings in the purity of its text as actually transmitted and kept in use, but also in the abundance of testimony which has come down to us for castigating its comparatively infrequent blemishes.”14

“The great mass of the New Testament…has been transmitted to us with no, or next to no, variation.”15

Richard Bentley (1662-1742)

- English classical scholar, critic, and theologian

- Master of Trinity College, Cambridge

- First Englishman to be ranked with the great heroes of classical learning

- Known for his literary and textual criticism

- The “Founder of Historical Philology”

- Credited with the creation of the English school of Hellenism

“[T]he real text of the sacred writers does not now (since the originals have been so long lost) lie in any single manuscript or edition, but is dispersed in them all. ‘Tis competently exact indeed even in the worst manuscript now extant; nor is one article of faith or moral precept either perverted or lost in them.”16

“Make your thirty thousand various readings as many more, if numbers of copies can ever reach that sum; all the better to a knowing and serious reader, who is into the context, are so far from shaking the faith of the Christian, that they on the contrary confirm it.”17

Samuel Davidson (1806-1898)

- Irish Biblical Scholar

- Professor of Biblical Criticism at Royal College of Belfast

- Professor of Biblical Criticism in the Lancashire Independent College at Manchester

- Authored—

- A Treatise on Biblical Criticism

- Lectures on Ecclesiastical Polity

- An Introduction to the New Testament

- The Hebrew Text of the Old Testament Revised

- Text of the O.T. & Interpretation of the Bible

- Introduction to the Old Testament

- On a Fresh Revision of the Old Testament

- Canon of the Bible

“Having shewn the various attempts made to restore [the text] to its pristine purity, we may add a few words on the general result obtained. The effect of it has been to establish the genuineness of the New Testament text in all important particulars. No new doctrines have been elicited by its aid; nor have any historical facts been summoned by it from their obscurity. All the doctrines and duties of Christianity remain unaffected…. [T]he researches of modern criticism…have proved one thing—that in the records of inspiration there is no material corruption. They have shewn successfully that during the lapse of many centuries the text of Scripture has been preserved with great care; that it has not been extensively tampered with by daring hands…. [C]riticism has been gradually…proving the immovable security of a foundation on which the Christian faith may safely rest. It has taught us to regard the Scriptures as they now are to be divine in their origin…. [W]e may well say that the Scriptures continue essentially the same as when they proceeded from the writers themselves. Hence none need be alarmed when he hears of the vast collection of various readings accumulated by the collators of MSS. and critical editors. The majority are of a trifling kind, resembling differences in the collocation of words and synonymous expressions which writers of different tastes evince. Confiding in the general integrity of our religious records, we can look upon a quarter or half a million of various readings with calmness, since they are so unimportant as not to affect religious belief…. [T]he present Scriptures may be regarded as uninjured in their transmission through many ages.”18

Frederick H.A. Scrivener (1813-1891)

- Important textual critic of the New Testament

- Member of the English New Testament Revision Committee (Revised Version)

- Graduated Trinity College, Cambridge

- Taught classics at several schools in southern England

- Edited the Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis

- Edited several editions of the Greek New Testament

- Collated the Codex Sinaiticus with the Textus Receptus

- First to distinguish the Textus Receptus from the Byzantine text

“[O]ne great truth is admitted on all hands—the almost complete freedom of Holy Scripture from the bare suspicion of wilful [sic] corruption; the absolute identity of the testimony of every known copy in respect to doctrine, and spirit, and the main drift of every argument and every narrative through the entire volume of Inspiration…. Thus hath God’s Providence kept from harm the treasure of His written word, so far as is needful for the quiet assurance of His church and people.”19

Sir Frederic George Kenyon (1863-1952)

- Widely respected, eminent British paleographer and biblical and classical scholar

- Occupied a series of posts at the British Museum

- President of the British Academy from 1917 to 1921

- President of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem

- Made a lifelong study of the Bible as an historical text

“One word of warning…must be emphasized in conclusion. No fundamental doctrine of the Christian faith rests on a disputed reading. Constant references to mistakes and divergencies of reading…might give rise to the doubt whether the substance, as well as the language, of the Bible is not open to question. It cannot be too strongly asserted that in substance the text of the Bible is certain. Especially is this the case with the New Testament. The number of manuscripts of the New Testament, of early translations from it, and of quotations from it in the oldest writers of the Church is so large, that it is practically certain that the true reading of every doubtful passage is preserved in some one or other of these ancient authorities. This can be said of no other ancient book in the world.”20

“It is true (and it cannot be too emphatically stated) that none of the fundamental truths of Christianity rests on passages of which the genuineness is doubtful.”21

“The interval then between the dates of original composition and the earliest extant evidence becomes so small as to be in fact negligible, and the last foundation for any doubt that the Scriptures have come down to us substantially as they were written has now been removed.”22

“Both the authenticity and the general integrity of the books of the New Testament may be regarded as finally established.”23

“The Christian can take the whole Bible in his hand and say without fear of hesitation that he holds in it the true Word of God, faithfully handed down from generation to generation throughout the centuries.”24

Summary/Conclusions

- The nature of this subject is such that it matters not that we consider what scholars from a century or more ago have said—because if the integrity of the Biblical text was established and authenticated at that time, it remains so today.

- We can confidently affirm that we have 999/1000ths of the original New Testament intact; the remaining 1/1000th is inconsequential.

- The Bible has not been corrupted in transmission.

Endnotes

1 F.F. Bruce (1975 reprint), The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable? (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans), pp. 19-20.

2 F.F. Bruce (1963), The Books and the Parchments (Westwood, NJ: Fleming H. Revell), p. 178.

3 Ibid., p 189.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid., p. 181.

6 Interview in Lee Strobel (1998), The Case for Christ (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan), p. 59.

7 B.F. Westcott and F.J.A. Hort (1882), The New Testament in the Original Greek (New York: Harper & Brothers), p. 2.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid., pp. 2-3.

10 Ibid., p. 278.

11 Ibid., p. 284.

12 Ibid., p. 565.

13 J.W. McGarvey (1974 reprint), Evidences of Christianity (Nashville, TN: Gospel Advocate), p. 17.

14 Benjamin B. Warfield (1886), An Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament (London: Hodder & Stoughton), pp. 12-13.

15 Ibid., p. 13.

16 Richard Bentley (1725), Remarks Upon a Late Discourse of Free Thinking (Cambridge: Cornelius Crownfield), p. 68-69.

17 Ibid., p. 76.

18 Samuel Davidson (1853), A Treatise on Biblical Criticism (Boston, MA: Gould & Lincoln), pp. 147-148.

19 Frederic H.A. Scrivener (1861), A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament (Cambridge: Deighton, Bell, & Co.), pp. 6-7.

20 Sir Frederic Kenyon (1895), Our Bible and the Ancient Manuscripts (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode), pp. 10-11.

21 Ibid., pp. 3-4.

22 Sir Frederic Kenyon (1940), The Bible and Archaeology (New York: Harper & Row), pp. 288-289.

23 Ibid., pp. 288-289.

24 Our Bible…, pp. 10-11.

The post Has the Bible Been Corrupted?—What the Scholars Say appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>The post Q&A: Inconsistencies and Contradictions in the Bible? appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>“My son, who we raised to believe the Bible is the inspired Word of God, became liberalized some years ago. He claims that there are ‘thousands of inconsistencies and contradictions’ in the Bible. After some discussion, I at last challenged him to give me a list of ‘inconsistencies and contradictions’ that he considered significant, and I would try to give him an answer as to why they are not what he claims. He only respects theologians and scholars who have a Ph.D. in Greek or Hebrew. Please find his allegations below, taken from his email. Thank you for your willingness to help!”

#1: 1 John 5:7-8 is often referred to as the Johannine Comma because it was also obviously added by a later scribe and was not included in our most reliable and oldest manuscripts. The removal of this passage has two implications: (a) on the divinity of Jesus, and (b) on the existence of the trinity (see point #2).

Answer:

It is true that the Comma Johanneum is spurious.1 However, neither the divinity of Jesus nor the existence of the Trinity is at stake, since both of these doctrines are taught in other passages that are not under dispute. The deity of Christ is taught repeatedly in both the Old and New Testaments. For example, the Gospel of John is devoted entirely to the topic (see the thematic statement in 20:30-31), as is Colossians with its forthright affirmation: “For in Christ all the fullness of the Deity lives in bodily form” (2:9, NIV). The doctrine of the Trinity is clear from such passages as Matthew 3:16-17 and 28:19.2

#2: John 1:1-18 is often called the Prologue of John’s gospel. However, the passage is missing from most of our oldest and most reliable manuscripts. Its absence could significantly impact the theological understanding of Jesus as God and who has existed from the beginning with the Father.

Answer:

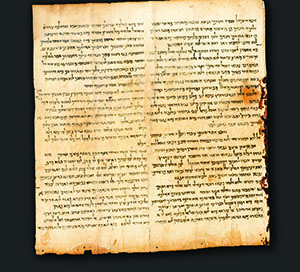

I am puzzled at the claim that the prologue to John’s Gospel (1:1-18) is “missing from most of our oldest and most reliable manuscripts.” That is simply not true. There are scattered textual variants3 within that pericope, but the section itself is not missing from the “oldest and most reliable manuscripts.” For example, in Codex Vaticanus, Luke ends at the bottom of the 2nd column. John begins at the top of the 3rd column and contains John 1:1-14 (vss. 14ff. continue on the next page). See Figure 1.

What’s more, the discovery of p66 and p75 only strengthens the case for the deity of Christ in John 1:18. Both of those papyrus manuscripts (which date from the 2nd/3rd centuries) have theos (God) instead of uios (son), as indicated in the NASB: “No man has seen God at any time; the only begotten God, who is in the bosom of the Father, He has explained Him”—a tremendous affirmation of Christ’s deity.

#3: Regarding Jesus’ humanity, there is significant evidence that numerous passages were added by later scribes in an effort to bolster the tenet of Jesus’ humanity in response to certain docetic “heresies” (specifically Marcion) during the 2nd century.

(a) In Luke 22:43-44 Jesus is said to be in agony in prayer to the point where his “…sweat became like drops of blood…” Most textual critics believe this is an addition to articulate Jesus’ humanity. It is also missing from most of our most reliable manuscripts.

Answer:

It is true that Luke 22:43-44 has strong manuscript support against its authenticity (although a majority of the committee for the UBS Greek Text decided to retain the passage due to its evident antiquity). However, once again, neither the humanity nor deity of Christ is jeopardized by this passage, whether the verses are genuine or not. The Bible clearly teaches that Jesus, being God, became flesh (John 1:14). So I fail to see how the addition of verses by well-meaning scribes that emphasize Jesus’ humanity in any way jeopardizes the authenticity of the New Testament.

(b) Luke 22:17-19, another well-known account of Jesus’ humanity (which also has some doctrinal implications regarding salvation), is Luke’s account of the last supper. Most of our oldest Greek manuscripts, as well as many Latin translations, render the passage, “And taking a cup, giving thanks, he said, ‘Take this and divide it among yourselves, for I say to you that I will not drink from the fruit of the vine from now on, until the kingdom of God comes.’ And taking bread, giving thanks, he broke it and gave it to them, saying, ‘This is my body. But behold, the hand of the one who betrays me is with me at the table.’”

However, after Jesus says, “This is my body…” later manuscripts have added (and these additions are now reflected in most of our current translations) “‘…which has been given for you; do this in remembrance of me’; And the cup likewise after supper, saying ‘this cup is the new covenant in my blood which is shed for you.’”

The absence of this passage de-harmonizes the gospels, removes Jesus’ institution of Communion, removes Jesus’ claim that it’s his blood that saves us, and removes one more “evidence” of Jesus’ humanity. The fact that the validity of this passage is suspect poses a problem for many theologians.

Answer:

The UBS Greek Text committee supports the longer reading as genuine in Luke 22:17-20. As Metzger noted: “the longer, or traditional, text of cup-bread-cup is read by all Greek manuscripts except D and by most of the ancient versions and Fathers.”4 Even if verses 19b-20 should be omitted, they in no way alter New Testament teaching, since almost the same words occur in 1 Corinthians 11:24b-25. The cup-bread-cup sequence was aptly explained over a century ago by Sir Frederick Kenyon,5 and neither the inclusion nor omission of 19b-20 “de-harmonizes the gospels.” Nor do they “remove” the Lord’s Supper, since the same is taught in Matthew 26:26ff., Mark 14:22ff., and 1 Corinthians 11:23ff. Nor is Jesus’ claim that His blood saves us removed, since the same is affirmed elsewhere repeatedly in the New Testament, including Matthew 26:28, 1 Corinthians 10:16; 11:25, and 1 Peter 1:19. And, again, Jesus’ humanity is hardly jeopardized. Read John 6:51, Colossians 1:22, Hebrews 10:5, 1 Peter 2:24, and 1 John 4:2-3.

(c) Luke 24:12 has been added in most recent manuscripts though this passage is not present in our oldest manuscripts. Additionally, the style of the writing is significantly different than the rest of Luke. Not only does the passage evidence Peter’s belief that Jesus had risen, but also provides strong evidence that Jesus was human.

Answer:

Luke 24:12 is supported overwhelmingly by the external evidence, including p75 (3rd century), the “Big Three” (Vaticanus, Alexandrinus, and Sinaiticus), as well as a host of other uncials, minuscules, and versions. So the claim that it is “not present in our oldest manuscripts” is mistaken. The difference in style is explicable on the grounds that both Luke and John received essentially the same information from the Holy Spirit. After all, John 20:3-6 reports the same details. Certainly, no reason exists to conclude that Peter’s belief in the resurrection or Jesus’ humanity are in jeopardy. Peter witnessed several post-resurrection appearances of Jesus in addition to the Luke 24:12 incident, e.g., Luke 24:34,36ff., John 20:19,26, Acts 1:9,22, and 1 Corinthians 15:5.

(d) Luke 24:51-52 is also not present in our oldest manuscripts. The style of writing is significantly different than what most scholars consider to be the “original” Luke. The absence of this passage decreases the argument for the humanity of Jesus as well reducing the argument for Jesus’ resurrection.

Answer:

Luke 24:51-52 is, once again, supported by the most prestigious Greek texts. Both verses are supported by p75 as well as Alexandrinus, Vaticanus, Sinaiticus, and a host of other Greek manuscripts, versions, and patristic writers. Writing style is somewhat subjective. But, again, the main point is that the doctrines of Jesus’ humanity and resurrection are in no way jeopardized by either the inclusion or exclusion of these verses.

Conclusion

Observe carefully: The solutions to these differences are detectable. Even if we were unable to decide between two readings of a passage and determine with certainty which one was the original, we know we have the Word of God—since the original reading is one or the other of the readings. The fact is most variants are solvable. But even if they were not, be reminded that absolutely no doctrine of Christianity is at stake in any textual variant. The vast majority of textual variants involve minor matters. The rest do not affect doctrine as it relates to one’s salvation. Even in those passages where an important doctrine might be deemed involved, that doctrine is affirmed in other passages where no variant is involved. I repeat: no doctrine of the Christian religion that has anything to do with salvation is in jeopardy due to the existence of textual variants. We can say with complete confidence that we have the New Testament as God intended. The Bible has not been corrupted.

The foremost textual critics of the last 200 years—the very men who are most familiar with this subject and who literally devoted their lives to poring over Greek manuscripts and becoming experts in textual criticism—have forthrightly declared the truth on this entire affair. Here are a few:

“[T]he superstructure of religion may be built with full hope and confidence that it rests on an authentic text.”6

“The variant readings about which any doubt remains among textual critics of the N.T. affect no material question of historic fact or of Christian faith and practice.”7

“All the authority and value possessed by these books when they were first written belong to them still.”8

“The interval then between the dates of original composition and the earliest extant evidence becomes so small as to be in fact negligible, and the last foundation for any doubt that the Scriptures have come down to us substantially as they were written has now been removed. Both the authenticity and the general integrity of the books of the New Testament may be regarded as finally established.”9

“[T]he great bulk of the words of the New Testament stand out above all discriminative processes of criticism, because they are free from variation, and need only to be transcribed…. [T]he words in our opinion still subject to doubt can hardly amount to more than a thousandth part of the whole New Testament.”10

Did you catch that? Westcott and Hort, prominent textual critics at the end of the 19th century, declared that—even at that time—we could confidently affirm that we have 999/1000ths of the original New Testament intact. The remaining 1/1000th is of no doctrinal consequence. Nothing has occurred since that time that alters their conclusion. The millennia-old allegation that the Bible contains “thousands of inconsistencies and contradictions” is simply not true. Case closed.

Endnotes

1 For an excellent treatment of this variant, see Guy N. Woods (1962), A Commentary on the New Testament Epistles of Peter, John, and Jude (Nashville, TN: Gospel Advocate Co.), pp. 324-326.

2 For a discussion of the Trinity, see Kyle Butt (2015), “The Trinity,” Reason & Revelation, 35[10]:110-112,116-119.

3 I.e., conflicting readings between manuscripts involving a word, verse, or verses. For more on this subject, see Dave Miller (2019), “Has the Bible Been Transmitted To Us Accurately?,” Reason & Revelation, 39[10]:110-113,116.

4 Bruce Metzger (1975), A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (London: United Bible Societies), pp. 173-174.

5 Sir Frederic Kenyon (1912), Handbook to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament (London: Macmillan), second edition, p. 349.

6 Ibid., p. 369.

7 F.F. Bruce (1975 reprint), The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable? (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans), pp. 19-21.

8 J.W. McGarvey (1974 reprint), Evidences of Christianity (Nashville, TN: Gospel Advocate), p. 17.

9 Sir Frederic Kenyon (1940), The Bible and Archaeology (New York: Harper & Row), pp. 288-289, emp. added.

10 B.F. Westcott & F.J.A. Hort (1885), The New Testament in the Original Greek (London: Macmillan), pp. 564-565, emp. added.

The post Q&A: Inconsistencies and Contradictions in the Bible? appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>The post Why So Long for the New Testament to be Written? appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>Why did God wait approximately 20 years after the Church was established to begin writing the New Testament? Why such a long span of time?

A:

Normally when we discuss the penning of the New Testament, we do so in view of the fact that God inspired men to write about Jesus and His will for the Church within only about 20-65 years of the Savior’s death and resurrection. Perhaps even more impressive is the abundant amount of evidence for the New Testament’s first-century origin. Due to the volume of ancient manuscripts, versions, and citations of the New Testament documents, even many liberal scholars have conceded the fact that the New Testament must have been completed by the end of the first century. Whereas the extant copies of Plato, Thucydides, Herodotus, Tacitus, and many others are separated from the time these men wrote by 1,000 years, manuscript evidence for the New Testament reaches as far back as the early second century, which has led most scholars to rightly conclude that the New Testament is, indeed, a first-century production.1 As Irwin H. Linton concluded regarding the gospel accounts: “A fact known to all who have given any study at all to this subject is that these books were quoted, listed, catalogued, harmonized, cited as authority by different writers, Christian and Pagan, right back to the time of the apostles.”2

Still, some wonder why God chose to wait approximately 20 years to begin writing the New Testament. Why didn’t the first-century apostles and prophets begin penning the New Testament as soon as the Church was established?

The simple, straightforward answer is that we cannot say for sure why God waited two decades to begin penning the New Testament. [NOTE: Conservative scholars generally agree that the earliest written New Testament documents, including Galatians and 1 and 2 Thessalonians, were likely written between A.D. 48-52.] We could ask any number of things regarding why God did or did not do something: Why did God wait some 2,500 years after Creation and some 1,000 years after the Flood to write a perfect, inspired account of these events? Why did God only spend 11 chapters in the Bible telling us about the first, approximately 2,000 years of human history, and 1,178 chapters telling us about the next 2,000? Why did God discontinue special, written revelation for over 400 years (between Malachi and the New Testament)? There are many questions, even specific ones about the makeup of God’s written revelation, that we would like to know about that He simply has not specifically revealed to us.

Having made that disclaimer, we can suggest a few logical reasons why God waited to inspire first-century apostles and prophets to pen the New Testament. First, the early Church had the treasure of the Gospel “in earthen vessels” (2 Corinthians 4:7). That is, the apostles were miraculously guided by the Spirit in what they taught (Galatians 1:12; 1 Corinthians 2:10-16). The Spirit of God guided them “into all Truth” (John 16:13). Also, those on whom the apostles chose to lay their hands in the early churches received the miraculous, spiritual gifts of prophecy, knowledge, wisdom, etc. (Acts 8:14-17; 1 Corinthians 12:1-11). Even though the Church was without the inspired writings of Paul, Peter, John, etc. for a few years, God did not leave them without direction and guidance. In a sense, they had “walking, living New Testaments.” When the miraculous-age ended (1 Corinthians 13:8-10),3 however, the Church would need some type of continual guidance. Thus, during the miraculous age, God inspired the apostles and prophets to put in permanent form His perfect and complete revelation to guide the Church until Jesus’ return (cf. 2 Timothy 3:16-17).

Second, it was necessary for God to wait a few years to write the New Testament, and not pen it immediately following the Church’s establishment, because the books and letters that make up the New Testament were originally written for specific audiences and for specific purposes (though they are applicable to all Christians). For example, the epistles that Paul wrote to the church at Corinth could not have been written until there was a church at Corinth. If the church at Corinth was not established until the apostle Paul’s second missionary journey (ca. A.D. 49-52), then Paul obviously wrote to the Christians in Corinth after this time. Furthermore, since in 1 Corinthians Paul dealt with specific problems that had arisen in the church at Corinth (e.g, division, immorality, etc.), he could not have explicitly addressed these matters in detail until after they had come to pass. Thus, there was a need for time (i.e., a few years) to pass before the New Testament documents were penned.

Although some may be bothered by the fact that God waited approximately 20 years to begin penning the New Testament through His inspired writers, we can rest assured that He had good reasons for this relatively brief postponement. Admittedly, God did not explicitly indicate why He delayed putting His last will and testament in written form. Yet, logical reasons exist—most notably, the fact that the documents that make up the New Testament were written to specific peoples and for specific purposes.

Endnotes

1 Cf. F.F. Bruce (1953), The New Testament Documents—Are They Reliable? (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans), fourth edition; Norman L. Geisler and William E. Nix (1986), A General Introduction to the Bible (Chicago, IL: Moody), revised edition; Philip W. Comfort and David P. Barrett (2001), The Text of the Earliest New Testament Greek Manuscripts (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House).

2 Irwin H. Linton (1943), A Lawyer Examines the Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker), sixth edition, p. 39.

3 Cf. Dave Miller (2003), “Modern-Day Miracles, Tongue-Speaking, and Holy Spirit Baptism: A Refutation—Extended Version,” Apologetics Press, http://www.apologeticspress.org/apcontent.aspx?category=11&article=1399.

The post Why So Long for the New Testament to be Written? appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>The post The Integrity of the Biblical Text (Part 3): Text of the Old Testament appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>[Editor’s Note: This article is the third installment in a three-part series pertaining to the integrity of the biblical text through the centuries. AP auxiliary writer Dr. Rogers serves as Director of the Graduate School of Theology at Freed-Hardeman University. He holds an M.A. in New Testament from FHU as well as an M.Phil. and Ph.D. in Hebraic, Judaic, and Cognate Studies from Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion.]

The Old Testament was written over a span of about 1,000 years by approximately 30 different authors (most of whom are anonymous) in at least three different countries (Egypt, Israel, and Babylon) in two different languages (Hebrew and Aramaic). We have nothing that any of the biblical authors personally wrote, nor do we even have a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy. In fact, we cannot know for certain how many steps removed our earliest manuscripts are from the originals. All of these facts pose serious challenges to those who wish to know what the Holy Spirit originally inspired (cf. 2 Timothy 3:16).

Sensing vulnerability, critics of the Bible continue to pound away at the anvil of skepticism. They deny the possibility of any knowledge of the original text of the Bible. They remind us that some literature (especially the Prophets) originated orally, and allege we cannot know how accurately it was written. We cannot know whether or not the Bible substantially changed over the course of its transmission through time. We cannot know whether some inspired books were lost (the Bible makes numerous references to books we no longer possess). Therefore, we cannot know what to believe. How do people of faith respond to such assertions?

Can we know with any degree of confidence that we have the Bible? Can we use the evidence available to reconstruct the text of the Old Testament? These simple questions involve complex answers. In this article we shall attempt to emphasize the challenges inherent in establishing the text of the Old Testament. We shall also argue that, despite these challenges, we can, indeed, have confidence in how we got the Old Testament.

The Manuscripts of the Old Testament

The two great codices of the Hebrew Bible are the Aleppo Codex (10th century A.D.) and the Leningrad Codex (11th century A.D.). These both represent the Masoretic text type, and are excellent copies. The Masoretes were Jewish scholars and textual critics who sought to preserve the traditional pronunciation of the Hebrew text. This led them to develop a system of vowel “points” to assist in pronunciation. The value of their work is that they did not wish to change the consonantal writing of the text (Hebrew, even today, is not traditionally written with vowels). The system of ketiv (pronounced, k-TEEV) and qere (pronounced k-RAY), the former meaning “what is written” and the latter “what is read,” explains that the Masoretes recognized there were transcriptional errors in the Bible, but these were not to be read since most make no sense at all in Hebrew. The fact that the Masoretes were willing to preserve the text, even when they knew it contained copying mistakes, tells us how seriously they took their work. They viewed themselves as mere transmitters, like modern copy machines. They transmitted exactly what they received.

Although the Masoretes worked in the Middle Ages, most scholars believe the basic text with which the Masoretes worked had become standard by the first century A.D. In fact, of the biblical manuscripts discovered in the area of the Dead Sea (excluding the site of Qumran), all of them match the later Masoretic text. This should give us a great deal of confidence in the text of the Old Testament. At Qumran, the so-called “proto-Masoretic” text type is the most prominent, although a greater variation can be observed here than at other Judean desert sites. This points to the careful copying of the Hebrew Bible.

All English translations today are essentially reflections of the Masoretic Hebrew text, and, if the Dead Sea Scrolls are consulted at all, they are usually accounted for in the footnotes (see especially the RSV and ESV). This is due to the fragmentary nature of the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the uncertainty of using the ancient translations (such as the Septuagint) as a means to reconstruct what the Hebrew might have said. While we would love to discover the original autograph of any biblical book, the closeness of most of our earliest biblical manuscripts to those of Medieval times furnishes us a reason to have confidence in the accuracy of the transmission of our Old Testament.

The Aleppo Codex

The Aleppo Codex has a fascinating history. It was carefully copied sometime in the early 10th century A.D., and contains what was then the recent refinement of Masoretic vowel points by Aaron ben Moses ben Asher (10th century A.D.), whom the Jews regard as the greatest of Masoretic grammarians. A book of great value, it was housed in Jerusalem during the First Crusade (A.D. 1096-1099) before it was taken by the Crusaders and held for ransom. Finally released undamaged, the Codex came to rest in Egypt for the next 200 years. After this it was apparently taken to Aleppo, Syria, where it was carefully guarded for the next 600 years. Even the great textual critic Paul Kahle, former editor of the standard academic edition, Biblia Hebraica, was denied access to the Codex.

After the United Nations resolved to form the modern State of Israel in 1947, anti-Jewish riots broke out in Syria, leading the Arab population of Aleppo to burn the Great Synagogue where the Codex was housed. After this point, the story becomes nebulous. What we know for certain is that the Codex was complete or nearly complete before the riot, and today, 196 of the original 491 pages are missing. Some allege that fire destroyed these pages, but those who have closely examined the Codex find little evidence of fire damage. Others allege that pages were intentionally torn from the Codex, perhaps in an effort to save as much as possible in the midst of a precarious situation. 118 of the 196 missing pages are from the Pentateuch (the oldest and holiest part of Scripture for the Jews), and a few individual leaves have emerged through the decades. This evidence suggests that concerned Jews did in fact tear pages from the Codex likely in an effort to save them. But whether these rescued pages will ever come to light is impossible to say.

The significance of the Aleppo Codex lies in its largely complete nature for many biblical books. 295 pages survive. Only 12 books are missing completely (Genesis–Numbers, Ecclesiastes, Lamentations, Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah, Obadiah, Jonah and Haggai), although others are missing parts (Deuteronomy, 2 Kings, Psalms, Song of Songs, Jeremiah, Amos and Micah). Still, it is the best Masoretic manuscript in existence.

The Leningrad Codex

The early 11th century Leningrad Codex is today housed in St. Petersburg, Russia (“Leningrad” under the former Soviet Union). This copy, like the Aleppo Codex, belongs to the Ben Asher family of Masoretic Hebrew manuscripts, and serves as the basis for the standard Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia and the more recent Biblia Hebraica Quinta, the standard academic editions from which most modern Old Testament translations come. The Hebrew University Bible Project, on the other hand, has elected to utilize the Aleppo Codex as its primary base text. Although scholars generally regard the Aleppo Codex as more reliable, the two manuscripts are extremely similar. The Leningrad Codex holds the distinction of being the oldest complete Hebrew Bible known to exist, although it is not even 1,000 years old.

The Nash Papyrus

We now turn from more or less complete copies of the Bible to fragments. Acquired in 1902, the Nash Papyrus (so named from Walter Llewellyn Nash who purchased it) dates to the late 2nd century B.C., and was the oldest copy of any part of the Old Testament text known before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The manuscript is small, being about 5.5 inches tall and a little over 2 inches wide (see Figure 1). Only 24 lines are legible, and these represent the Ten Commandments and part of the Shema‘ (pronounced sh-MAH) extracted from Deuteronomy 5 and 6. Some have suggested the text was a phylactery due to its size (cf. Matthew 23:5).

One interesting difference between the Nash Papyrus and the received Hebrew text is the former’s absence of “the house of slavery” in reference to Egypt (Deuteronomy 5:6). Some have alleged that, since the papyrus likely originated in Egypt, the scribe wished not to offend his homeland with such a reference, and so removed it. If the Nash Papyrus is a personal copy intended for private use, we might assume that the strict rules about the sanctity of every word of Scripture did not apply quite as strictly as it might for a synagogue copy (cf. Deuteronomy 8:3; Matthew 5:18). However, it is also possible (although less likely) that the parent-text (what the Germans call the Vorlage) did not contain these words and the scribe of the Nash Papyrus is copying what was in front of him.

The Silver Scrolls from Ketef Hinnom

In 1979 two small, silver scrolls containing the Priestly Blessing (Numbers 6:23-26) were found in an excavation near Jerusalem. The larger of these texts measures just one inch in width and not quite four inches in length. The smaller is a half-inch in width and about an inch and a half in length. Despite their size, these texts, which date to the 7th century B.C., represent the oldest copies of any part of the biblical text we possess. Ironically, they seem to have been intended as amulets to ward off evil spirits (cf. Isaiah 3:20; Ezekiel 13:18,20).

The Dead Sea Scrolls

The oldest of the biblical manuscripts among the Dead Sea Scrolls date to the mid-3rd century B.C., and the latest date to the 1st century A.D. 4QExod–Levf (4Q17) and 4QSamb (4Q52) are the two oldest known to exist, and both date to the mid-3rd century B.C. The former probably once contained the entire Pentateuch, but now includes only five fragments totaling 259 words. The latter contains about 23 fragments and represents various sections of 1 Samuel 12-23. The Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa) is the only one of the biblical Dead Sea Scrolls to survive in its entirety. Because of the fragmentary nature of the evidence, it is impossible to compile a complete Hebrew Bible from the Dead Sea Scrolls. So, while of tremendous value, our ability to apply what we learn from the Dead Sea Scrolls is limited.

The fragments that do exist offer a number of variant readings. While none of these variants alters the theology of the Old Testament, many of them are noteworthy. For example, traditional English translations set the height of Goliath at six cubits and a span, following the Masoretic Hebrew Text (1 Samuel 17:4). But the oldest Hebrew copy of the Goliath story of Samuel, 4QSama, agrees with the Septuagint that Goliath’s height was four cubits and a span. This drops the height of Goliath from about nine and a half feet to about six and a half feet! The oldest reading is perhaps the original reading.

Another example can be provided from the Great Isaiah Scroll. In Isaiah 53:11 1QIsaa agrees with the Septuagint, reading, “From the anguish of his soul he shall see light and be satisfied.” The Masoretic Hebrew, represented in most English translations, does not have the word “light.” It is uncertain whether the word “light” has been inserted into the Isaiah Scroll or removed from the Masoretic Hebrew. So, in this case, we cannot be certain what the original reading was.

There are a few occasions in which we know material is missing in the Masoretic Hebrew text. For example, Psalm 145 is an acrostic Psalm in which each line begins with the succeeding letter of the Hebrew alphabet (ד ,ג ,ב ,א, etc.). The problem is that the line beginning with the letter nun (נ) is missing. 11QPsa, the only Dead Sea Scrolls Psalms manuscript to cover Psalm 145, has the nun verse: “God is faithful in his words and gracious in all his works.” It just so happens again that the missing verse matches what was already preserved in the Septuagint long ago. There is no question the Septuagint and the Dead Sea Scrolls preserve the original reading.

I do not wish to give the impression that the Dead Sea Scrolls always agree with the Septuagint. In fact, Emanuel Tov states that no single Qumran manuscript can be regarded as the parent text of any book translated into its Septuagint Greek form. Rather, Tov offers the following statistics: of the Pentateuch, only 46 manuscripts provide a sufficient basis for analysis. Of these manuscripts, 27 (nearly 60%) clearly anticipate the later Masoretic Text, while only one generally matches the Septuagint. The remaining 18 cannot be aligned with any known textual tradition (39%). Of the remaining books of Scripture, 75 manuscripts are sufficient for analysis. Of these, 33 anticipate the Masoretic Text (44%) while only five reflect the text represented by the Septuagint. Among these manuscripts Tov regards 37 as unaligned (49%). In other words, manuscripts matching the later Masoretic text are dominant.

Of course, the various textual traditions are not as divergent as one might be led to believe by these statistics. Textual criticism is concerned with minute details such as the presence or absence of letters or the division of words. For example, “valley of the shadow of death” (Psalm 23:4) assumes the Hebrew צל מות, but the Hebrew text actually has צלמות, meaning “deathly darkness.” The difference in definition hangs on a single space in a word, and not on a different text! Another example would be the spelling of Moses as משה or מושה, or David as דוד or דויד. These spelling differences count as variants, but in no way change the meaning. It should also be stressed that statistical analyses, such as those cited above, tend to be highly subjective, and many others are bound to disagree. Further discoveries could substantially alter what we think we now know. Humility is always appropriate in the field of textual criticism. Still, the plurality of various Old Testament texts at Qumran seems to match a similar variety with Old Testament quotations in the New Testament. There was no “authorized version” of the Bible at the time of Jesus.

Textual Plurality and New Testament Quotations

We have striven thus far to show the Hebrew Bible did not exist in one pristine form at the time of the New Testament. Were the New Testament authors aware of this situation? If so, how do they handle the textual variety? It seems clear that the New Testament authors both respected and utilized the textual variety in existence. The New Testament quotations sometimes match the Masoretic Hebrew exactly (e.g., Mark 14:23 ~ Isaiah 53:12), sometimes match the Septuagint exactly (e.g., Mark 7:6–7 ~ Isaiah 29:13), sometimes agree more with the Dead Sea Scrolls (e.g., Romans 15:10 ~ Deuteronomy 32:43 [= 4QDeutq), and sometimes match nothing else known (i.e., they are “unaligned” in scholarly parlance; e.g., Romans 1:17; Galatians 3:11 ~ Habakkuk 2:4).

There are times when the Greek translation is actually a clearer reflection of the Divine intent than the Hebrew original. For example, to refute the Sadducees, Jesus quotes the Septuagint form of Exodus 3:6: “‘I am the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.’ God is not the God of the dead, but of the living” (Matthew 22:32). The Hebrew language has no present tense verb, and thus the “I am” verb is missing in the Hebrew text of Exodus 3:6 (note the NKJV italicizes the word “am” in Exodus 3:6, indicating its absence in the Hebrew text). In order to leave no doubt about the meaning, Jesus cites the Greek form of the verse (which specifies the present tense).

There are other occasions when the New Testament authors might generalize a verse by altering it slightly. Paul’s quotations of Habakkuk 2:4 could fall into this category. The Masoretic Hebrew reads, “The just shall live by his faith,” which can be understood either as the faithfulness of the just man or the faithfulness of God. The Septuagint clarifies, “The just shall live by my faith,” unambiguously referring to God. The difference between the possessive pronouns “his” and “my” is just one stroke of one letter in Hebrew (“his” = ו and “my” = י). These letters are often confused in Hebrew manuscripts (to the sympathetic comfort of many elementary Hebrew students!), and it appears Paul here wishes both to eliminate the textual confusion and generalize the truth of the verse with the more abstract, “The just shall live by faith” (Romans 1:17; Galatians 3:11).

The way the New Testament authors used the various versions of the Scriptures is not unlike the way many preachers use English translations. I have heard the sermons of several who prefer the King James Version but switch to the American Standard Version when preaching on Psalm 119:160a. The former reads, “Thy word is true from the beginning,” while the latter states, “The sum of thy word is truth.” Since the Hebrew is ambiguous (literally, “the head of your word is true [or truth]”), either translation can be regarded as possible. But most would opt for the passage that “preaches” better or makes a clearer point. In the absence of certainty, perhaps it is not foolish to follow such a course, even though modern translators (and preachers!) do not have the benefit of inspiration. The bottom line is this: despite minor differences across the manuscripts, the Old Testament is remarkably—one might say providentially—preserved and transmitted.

Conclusion

The text of the Old Testament was both confirmed and complicated by the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Septuagint likewise supports the basic content of the traditional Hebrew, but also contains some differences that need not be overlooked. Modern translations of the Old Testament generally take into account all of the evidence, exercising their best judgment when it seems there may be a mistake in transmission of the Masoretic Hebrew. For example, Genesis 47:21 in the Masoretic text seems to have mistaken the letter daleth (ד) for resh (ר), an understandable mistake, as these letters are very similar in appearance. The RSV and ESV have elected to follow the ancient versions (Samaritan Pentateuch, Septuagint, and Latin Vulgate) while the KJV and ASV choose to translate the Masoretic Hebrew, in spite of its apparent mistake. Again, in 1 Samuel 1:24, almost all the modern versions read “three-year-old bull” as opposed to the KJV and NKJV which have “three bulls.” The KJV tradition follows the Masoretic Hebrew (even though it is difficult to imagine Hannah dragging three bulls to Shiloh!), while the modern versions follow 4QSama, the Septuagint, and the Syriac traditions. The oldest text makes better sense in this case.

The evidence suggests we should exercise good judgment in our reading of the Old Testament, as the New Testament authors seem to do. Only in a handful of cases are there differences in the textual traditions worth noting, and even then the differences concern minute details that, while important to textual critics, do not alter any major teaching of the Old Testament. It appears that God has provided us with an Old Testament text substantially accurate in all we need to know about His character and His will.

Critics who allege we cannot know the text of the Bible must resort to building mountains out of molehills. Let them produce one variant reading from the Old Testament that substantially alters a theological point affirmed by Jesus or the Apostles. The basic differences in the textual traditions of the Old Testament can be compared to the differences in English translations. While one person’s Bible might have a different word or phrase here and there, the substantial message of God’s Word remains the same.

Endnotes

1 Just to cite a few examples, Numbers refers to the “Book of the Wars of the Lord” (Numbers 21:15). Joshua refers to the “Book of Jashar” (Joshua 10:13), and 2 Chronicles 9:29 alone refers to three different works: the “Words of Nathan the Prophet,” the “Prophecy of Ahijah the Shilonite,” and the “Visions of Iddo the Seer.”

2 See Emanuel Tov (2001), Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press), second revised edition, p. 108.

3 For a fascinating account of the history of the Aleppo Codex, see Hayim Tawil and Bernard Schneider (2010), The Crown of Aleppo: The Mystery of the Oldest Hebrew Bible Codex (Philadelphia, PA: JPS), and more popularly, Matti Friedman (2013), The Aleppo Codex: In Pursuit of One of the World’s Most Coveted, Sacred and Mysterious Books (New York: Algonquin Books).

4 For a convenient translation of the biblical Scrolls, see Martin G. Abegg, Jr. and Peter Flint (2002), The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible: The Oldest Known Bible Translated for the First Time into English (San Francisco, CA: Harper).

5 4QSama is a strange manuscript, containing 81 variants that match no other known Samuel text (see Donald W. Parry (2002), “Unique Readings in 4QSama,” in The Bible as Book: The Hebrew Bible and the Judaean Desert Discoveries, ed. Edward D. Herbert and Emanuel Tov [London: The British Library], pp. 209-217).

6 Tov, p. 108.

The post The Integrity of the Biblical Text (Part 3): Text of the Old Testament appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>The post Can I Trust the Numbers in Genesis 5? appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>[EDITOR’S NOTE: AP auxiliary writer Dr. Rogers is the Director of the Graduate school of Theology and Associate Professor of Bible at Freed-Hardeman University. He holds an M.A. in New Testament from Freed-Hardeman University as well as an M.Phil. and Ph.D. in Hebraic, Judaic, and Cognate Studies from Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion.]

The numbers in Genesis 5 have long raised challenges for readers of Scripture. The most obvious problem is with the surprisingly long lifespans recorded of ancient humanity. Many moderns simply find it difficult to believe anyone could live for 900 years! So that raises questions about the basic credibility of the Bible, or at least of the primeval history (Genesis 1-11).1 But Genesis 5 presents a more nuanced issue that does not appear obvious to readers of the Bible in modern translation. Because the standard modern-language versions translate the Masoretic Hebrew text primarily if not entirely, modern readers have no idea that the ancient translations vary quite strikingly in the numbers they provide. Before we begin our analysis of the situation, we might offer a brief word on the nature of the evidence. Then we will address the textual variations in Genesis 5.

The Masoretic Hebrew Text

The Hebrew Bible is extraordinarily ancient. The earliest parts were composed according to internal evidence as early as 1400 B.C. and the most recent around 430 B.C. This means the recovery of any original manuscript is all but hopeless. Indeed, the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls was a remarkable peek into fragments of the biblical text as old as the third century B.C. However, not enough remains from the Dead Sea Scrolls for us to compile a complete Hebrew Bible.2 This means we are reliant on the Masoretic Text. The Masoretic Text is very close to that of the Dead Sea Scrolls in many cases, and was probably standardized among the rabbis after the time of the New Testament. One confirmation is Jerome’s Latin Vulgate translation of the Hebrew Bible (A.D. 390-410), which reflects with few significant variants the Masoretic Text.

The Septuagint

The “Septuagint” is the name assigned among ancient authors to the Greek translation of the Old Testament, although this is a misnomer. The term septuaginta in Latin means “70,” and the number comes from the 2nd-century B.C. Letter of Aristeas which reports that 70 Jewish translators (or 72) were sent from Jerusalem to Alexandria, Egypt for the purpose of translating the Pentateuch. Ptolemy II (reigned 283-246 B.C.) requested the translation because he wanted the best books in the world contained in the library of Alexandria. Aristeas, however, speaks only of the Pentateuch (not the rest of the books), and modern scholars find Aristeas’ narrative fanciful and unreliable (the Hebrew scroll from which the Septuagint was translated was written with letters of gold, for example). It is now widely believed that the entirety of the Old Testament was translated into Greek sometime between the third and first centuries B.C. although we do not know where, why, and by whom.

The Samaritan Pentateuch

The Samaritan community (which still exists today) produced its own Pentateuch, which is the only part of the Hebrew Bible it regards as sacred. Like the Masoretic Text, whose earliest manuscript dates to the 10th century A.D., the Abisha Scroll is the earliest preserved text of the Samaritan Pentateuch, and it dates no earlier than the 12th century A.D. It is commonly claimed that 6,000 differences exist between the Samaritan Pentateuch and the Masoretic Text, but most of these are spelling variations and other minor variants. The Samaritan Pentateuch does, however, include explicit information that squares with its own theology against traditional Jewish doctrine, such as a command to worship on Mount Gerizim (cf. John 4:20). The Dead Sea Scrolls sometimes support readings that match the Samaritan Pentateuch in contrast with the Masoretic Text (although about a third of these match the Septuagint as well). This suggests that the Samaritan community sometimes preserves an ancient Hebrew recension3 transmitted in no other textual tradition.

Comparing the Evidence

The three textual traditions we have discussed all receive support from different manuscripts and biblical quotations found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, although the Masoretic Text is clearly the most dominant. Therefore, it is important for scholars to compare and contrast the ancient evidence in order to arrive at the earliest text. Much of the time such comparisons yield clear results. But in the case of Genesis 5 it is more complicated. The textual traditions disagree in many cases. The situation is further complicated by the unfortunate fact that the biblical manuscripts discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls yielded no information sufficient for analysis in relation to the numbers of Genesis 5.

Table 1 offers a quick glance at the three texts. I take the Masoretic Hebrew as standard. Differences from the Masoretic Hebrew are noted in bold.

|

Person |

Masoretic Hebrew4 |

Septuagint |

Samaritan |

|

Adam |

130 + 800 = 930 years |

230+ 700 = 930 years |

130 + 800 = 930 years |

|

Seth |

105 + 807 = 912 years |

205 + 707= 912 years |

105 + 807 = 912 years |

|

Enosh |

90 + 815 = 905 years |

190 + 715= 905 years |

90 + 815 = 905 years |

|

Kenan |

70 + 840 = 910 years |

170 + 740= 910 years |

70 + 840 = 910 years |

|

Mahalalel |

65 + 830 = 895 years |

165 + 730= 895 years |

65 + 830 = 895 years |

|

Jared |

162 + 800 = 962 years |

162 + 800 = 962 years |

62 + 785 = 847 years |

|

Enoch |

65 + 300 = 365 years6 |

165 + 200= 365 years |

65 + 300 = 365 years |

|

Methuselah |

187 + 782 = 969 years |

167 + 802 = 969 years |

67 + 653 = 720 years |

|

Lamech |

182 + 595 = 777 years |

188 + 565 = 753 years |

53 + 600 = 653 years |

Several observations are in order. First, note that the Masoretic Hebrew and the Samaritan versions are largely in agreement. In only three places do we find discrepancies (Jared, Methuselah, and Lamech). Second, note that the Septuagint never agrees with the Samaritan version. This suggests no textual relationship between the two. It is true that the Septuagint agrees with the Hebrew version in its entirety only once. However, in every case except one, the disagreements concern the lesser numbers (the age of the patriarch at the birth of his first child plus the number of years from that point to his death). The Septuagint’s totals of the patriarchal lifespans are identical with the Masoretic Text (except with Lamech). Third, note that the ancient versions do not solve the alleged problem of the extreme ages of the patriarchs. The three differences in the Samaritan Pentateuch do in fact reduce the ages of three patriarchs, but is it any more believable that Methuselah, for example, lived to the age of 720 as opposed to 969?

How Did the Textual Corruption Occur?

A quick scan of the chart above obviously invites the question of textual corruption. All the texts cannot be right since they disagree. So which one is right, and how do we know? This question is impossible to answer with certainty, but perhaps we can offer a tentative explanation of how the corruption may have come to be.

First, according to our most ancient evidence (from Egypt and Babylonia), numbers were written pictographically. That is, numbers were symbols. This should not seem strange to us since the modern Arabic numerals are also symbols (1,2,3, etc.). Most ancient Near Eastern systems simply used tally marks for the first nine numbers (1= |, 2 = ||, 3 = |||, etc.). So to count 1–9 one needed simply to count tallies. The symbols change from there but the principle remains the same. In Hieroglyphic, for example, ⊓ is 10, but ⊓⊓ 20, ⊓⊓⊓ 30, and so on. The symbol changes again at 100, but the pattern repeats. Although symbolic variations exist among the various Near Eastern languages, the basic principles pretty well hold. This means by simply miscounting symbols, a scribe could be off by factors of 10 or even 100.

Most of the variations in the table above between the Septuagint and the Masoretic Text can be accounted for by a single scribe miscounting a single symbol. Of the Septuagint’s 17 differences, all but five can be attributed to miscounting a symbol for 100. This is a reduction of the variation over 70%! Although the numerical writing system does not account for every difference, it greatly reduces the number of variants.

Second, even after numbers are spelled in full, they remain subject to corruption in ancient manuscripts (not just the Bible). For example, no one today writes “one thousand and five hundred and eighty-seven.” Reading that number is much more confusing than reading “1,587.” Likewise, in ancient Hebrew one reads “two ten years and nine hundred years” in Seth’s case (912 years). Even assuming the numbers were initially transcribed accurately from the original, they could easily have been corrupted in the later manuscript tradition. The fact that the Samaritan Pentateuch and the Septuagint reflect greater variation toward the end of the patriarchal list may indicate scribal fatigue. The need to copy laboriously one number after the other may help to explain some of the problems in the transmission of numbers in Genesis 5.

Which Text Do We Believe?

While all ancient evidence of the text of Scripture is important, not all evidence is to be weighed equally. As a Greek translation, the Septuagint is one step removed from the Hebrew it translates. Since we do not have the manuscripts from which the Septuagint was translated, we cannot always know when the Septuagint reflects a different Hebrew text or when the translator(s) has made a mistake. The Samaritan Pentateuch has the advantage of being a Hebrew text that traces its lineage back to a very ancient textual tradition. But the Masoretic (or proto-Masoretic) Text is far more prominent among the Dead Sea Scrolls than the Samaritan version. This indicates the Samaritan tradition may be based on a fringe text considered inferior by the majority of Jews. Finally, the judgment of basically all English Bible translators since Jerome is not likely to be wrong. They have elected not to follow the Septuagint or the Samaritan Pentateuch for good reason. It is for good reason that the Masoretic Text is taken as the standard base for virtually all mainstream translations of the Old Testament.

Conclusion

The reader must keep in mind that all discussions concerning scribal errors and variations among manuscripts of the Bible may leave the impression that the text has been so corrupted that we cannot know God’s Word. This misimpression is understandable since textual criticism tends to focus on alleged problems of transmission and to ignore the remarkable accuracy with which the Bible has been copied. Hebrew scholar Bruce Waltke stresses that “in every era there was a strongtendency to preserve the text,”7 and that about “95 percent” of the Old Testament text is sound.8 If Waltke is correct, then textual critics deal only with about 5% of cases, and most of these involve problems that are easily solved.

I will conclude with an illustration. I can consult with many medical doctors, all of whom have legitimate education and licenses. But when it comes to a rare medical condition, surely I do not assume all doctors speak with equal authority. I respect the opinions of every medical professional, but I go to the Mayo Clinic for a reason: the treatment is generally regarded as better. The doctors are better educated and better able to diagnose and treat rare conditions. The numbers in Genesis 5 happen to be a rare case. It is unusual to find so much textual variation in the ancient evidence. In order to “heal” the differences in the text, I prefer to consult the textual tradition that is (1) oldest and (2) with the longest track record of trustworthiness. The Septuagint and the Samaritan Pentateuch are valuable textual traditions that ought to be respected. But they do not deserve the weight accorded the Masoretic Text. So, in the case of the numbers in Genesis 5, we cannot explain every variant (although we can give reasonable explanations for most). And all the numbers are extraordinarily high, at least from a modern perspective. Yet the Masoretic tradition deserves to be followed. You can trust your English translation.

Endnotes

1 See Appendix 2 in Creation Compromises (2000), (Montgomery, AL: Apologetics Press, second edition), pp. 357ff., http://apologeticspress.org/pdfs/e-books_pdf/cre_comp.pdf.

2 On the Dead Sea Scrolls see Justin Rogers (2019), “The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Bible,” Reason & Revelation, 39[11]:122-125,128-131, http://apologeticspress.org/apPubPage.aspx?pub=1&issue=1307.

3 A “recension” is a critical revision of an earlier text.

4 Most mainstream translations of the English Bible follow the Masoretic Hebrew closely.

5 I translate the Masoretic text and the Septuagint myself. I take the translation of the Samaritan Pentateuch from Benyamin Tsedaka, ed. (2013), The Israelite Samaritan Version of the Torah: First English Translation Compared with the Masoretic Version (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans).

6 All the ancient versions explain Enoch’s rather modest age as a result of the fact that “God took him” (i.e., he did not die).

7 Bruce K. Waltke, “How We Got the Hebrew Bible: The Text and Canon of the Old Testament,” pp. 27-50 in The Bible at Qumran: Text, Shape, and Interpretation, edited by Peter W. Flint (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001; the exact reference quoted here is found on p. 47).

8 Bruce K. Waltke, “Old Testament Textual Criticism,” pp. 156-86 in Foundations for Biblical Interpretation, edited by David S. Dockery, Kenneth A. Matthews, and R. Sloan (Nashville: Broadman and Holman, 1994; the exact reference quoted here is found on p. 158).

The post Can I Trust the Numbers in Genesis 5? appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>The post The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Bible appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>

[EDITOR’S NOTE: AP auxiliary writer Dr. Rogers is the Director of the Graduate School of Theology and Associate Professor of Bible at Freed-Hardeman University. He holds an M.A. in New Testament from Freed-Hardeman University as well as an M.Phil. and Ph.D. in Hebraic, Judaic, and Cognate Studies from Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion.]

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls is widely regarded as the greatest archaeological discovery of the 20th century. From 1947 to 1956 about 930 scrolls were found in 11 desert caves near Qumran, a site about 12½ miles southeast of Jerusalem. Other discoveries were made in about 11 other sites in the vicinity of the Dead Sea, but no place yielded the number of manuscripts as Qumran. The Qumran scrolls span four centuries, from the third century B.C. to the first century A.D., and are written in four languages, Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, and Nabatean, in addition to discovered coins having Latin inscriptions. The Dead Sea Scrolls are important for the Old Testament in at least two major ways: (1) they allow us access to Old Testament manuscripts over 1,000 years older than we previously knew; and (2) they provide information about the formation of the Old Testament canon of Scripture.

The Discovery and Publication of the Dead Sea Scrolls

The story has been told often.1 A Bedouin shepherd threw a rock into a cave, heard a crash, and discovered the Dead Sea Scrolls. This story is not entirely true. First of all, the broken jar and discovery of the cave took place two days before the first scrolls were found. There was not one Bedouin shepherd, but three. One threw the rock, and another entered the cave two days later without the prior knowledge of his partners. The shepherds took only a few scrolls, and they had no idea what they were and how much they were worth. The scrolls removed from what became known as Cave 1 were the “Great Isaiah Scroll” (1QIsaa), the Habakkuk commentary (1QpHab), and the Community Rule (1QS).2 These were slightly damaged in transportation before they could be sold to a dealer of antiquities, and to a Syrian Orthodox monastery.

When the number and value of the scrolls were determined, other caves continued to be looted and their contents sold by the Ta‘amireh tribe to which the shepherds belonged. Once the importance of the scrolls was determined, both scholars and governmental organizations (initially, of Jordan, and later, of Israel) became involved in discovering additional caves and conducting formal excavations. The site of Qumran was excavated in five consecutive seasons under the leadership of Roland De Vaux of the Jerusalem-based École Bibliques (1951-1956). Eventually, 10 more caves were discovered in the area of Qumran, Cave 4 alone yielding fragments of nearly 600 manuscripts.3

The laborious task of deciphering, editing, and publishing the Dead Sea Scrolls is a drama unto itself. The original scholars entrusted with the task of publishing the Scrolls were exclusively Christian, and thus the interests of early researchers tended toward Christian backgrounds and the relationship of the Scrolls to the New Testament. This fact irked many non-Christian scholars, especially the Israelis. With the additions of Israeli scholars Elisha Qimron and Emanuel Tov to the publication team in the 1980s, this problem was rectified, and now scholars from all backgrounds work on the Dead Sea Scrolls.

In addition to the racial issues, the early publishing team was small and very slow to do their work. Between 1950 and 1990 only seven of the eventual 40 volumes in Oxford University Press’s Discoveries in the Judean Desert series had been completed. In the 1990s alone, however, 20 additional volumes in this series appeared. There are two reasons for the proliferation in publication: First, Emanuel Tov of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem became the general editor of the series in late 1990. His appointment followed an anti-Semitism scandal that resulted in then-director John Strugnell of Harvard University being removed from the post. The scandal was provoked by Strugnell’s comments in the Israeli newspaper, Ha-aretz.4

Second, Ben Zion Wachholder of Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, Ohio, with the help of his student, Martin Abegg, produced a nearly complete text of the Scrolls from a previously published concordance.5 With the early use of computer databasing, Abegg was able to reverse-engineer the text of many Scrolls from the concordance. Although their publication was unauthorized both by the Israel Antiquities Authority and Oxford University, all agree their publication broke the hold on the Dead Sea Scrolls, and encouraged scholars to complete the work of official publication.6 Today all of the discovered, decipherable Scrolls have been published, and photographs of many of the Scrolls are available on the Internet.

This article provides two examples. Figure 1 is a photograph of two columns of the Great Isaiah Scroll, featuring Isaiah 53. This scroll is among the best preserved, and is not typical of the discovered manuscripts. Figure 2 is a more typical collection of fragments pieced together by specialists. Most of the Dead Sea Scrolls are, indeed, not so much scrolls as scraps.

|

|

| Figure 1: The Great Isaiah Scroll ( ISaiah 53) | Figure 2: A Portion of the Temle Scoll |

The Non-Biblical Manuscripts of the Dead Sea Scrolls

It surprises many people to hear the majority of the Dead Sea Scrolls are non-biblical. Of the approximately 930 scrolls discovered in the Judean desert, only 222 are biblical (i.e., less than 25%). The percentage of biblical scrolls is much higher at Judean desert sites other than Qumran. The biblical texts of Masada, for example, represent 47% of the total number of scrolls discovered.7 We may conclude Jews living in desert communities read many different books, and were not readers of the Bible alone. This does not necessarily mean, however, that secular books were read more than the Bible. In my personal library I have hundreds of books, but my Bibles take up only about a shelf and a half. Most of these books I do not read regularly, but my Bibles are in constant use. A similar situation might have existed for the Dead Sea communities. Still, the non-biblical Scrolls have relevance for how the Old Testament was understood and interpreted by some Jews prior to the time of the New Testament.

In order to better examine the non-biblical Scrolls, further classification is needed. So we shall first discuss works most certainly not written by members of the Qumran community, what Protestants might term “Apocrypha” as well as the so-called “Pseudepigrapha.” Then we shall turn to the “sectarian texts” that were either written by members of the Qumran sect or were formative for their development as a community.

Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha

The term “apocrypha” is a Greek plural substantive meaning “things hidden.” The term is borrowed from the Church Fathers who used it frequently to refer to books outside of the canon of Scripture recognized by the church. The term “pseudepigrapha,” by contrast, properly refers to writings “falsely ascribed.” Based on this meaning, the term pseudepigrapha ought to be applied to books such as 1 Enoch (which was not written by the real Enoch), the Wisdom of Solomon (not written by Solomon), and so on. But the collection commonly called Pseudepigrapha now stands for almost any non-canonical book that does not belong to the Old Testament or to the Protestant “Apocrypha.”

Of the Catholic Church’s “deuterocanonicals” (in Protestant terms, “Apocrypha”), the Dead Sea Scrolls preserve five copies of Tobit, three of the Wisdom of Jesus ben Sirah (Ecclesiasticus), and one of the so-called Epistle of Jeremiah (not actually written by Jeremiah). The position of the Pseudepigrapha is much better. The mysterious book of 1 Enoch is represented in 12 copies from Qumran, and the book of Jubilees in no less than 13 and possibly as many as 16 copies (depending on whether the fragments represent additional manuscripts). There are also at least five additional compositions related to Jubilees, further attesting its importance. By manuscript count alone, Jubilees is better represented than all but four of the canonical Old Testament books (Psalms, Deuteronomy, Isaiah, and Genesis). Some scholars have suggested that both 1 Enoch and Jubilees were accepted as canonical Scripture in Qumran. This is certainly possible, although perhaps it is best to leave the question open. Popularity does not require canonicity (see more below).

Sectarian Texts

The Dead Sea Scrolls discovery unveiled many works that were previously unknown. Since they are associated exclusively with the Qumran sect, they are normally called “sectarian.” Indeed, some of these works relate specifically to life in the sectarian community. The most important are the Damascus Document (CD) and the Rule of the Community (1QS), which best inform us about life in the community. Other texts are legal in nature, such as the Temple Scroll (11QT) and miksat ma‘asei ha-Torah (4QMMT), roughly translated “some matters of the Law.” This latter text lists grievances the Qumran community had with the Temple and its officials in Jerusalem.

It will surprise many readers to know that some of the Qumran scrolls were written in “cryptic scripts.” Scholars believe these scripts are, in fact, based on the Hebrew language, but have never deciphered them.8 The original editor of these texts distinguished three different cryptic scripts: “Cryptic A,” “Cryptic B,” and “Cryptic C,” respectively. As far as we know, these cryptic scripts are used nowhere else. But they were in prominent use at Qumran. The leader of the Qumran community (the maskil, or “understanding one”) most likely communicated in Cryptic A himself, which represents no less than 55 manuscripts. Cryptic B is found in two manuscripts, and the text of origin remains undeciphered. Cryptic C is found in only one manuscript. It utilizes the paleo-Hebrew alphabet and five additional letters that cannot be identified. The individual who manages to decipher these cryptic scripts will earn lasting fame in the pantheon of scholarship!