The post The Founders: Atheists & Deists or Theists & Christians? appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>But the real ignorance is seen in the misrepresentation of American history and the successful perpetration of one of the big myths of our time. Immediately after World War II, revisionist historians, who seem to have possessed an ardent hostility toward Christianity, were determined to expunge the role that God, the Bible, and the Christian religion played in the founding of America. Nevertheless, an honest seeker of truth may overcome their big myth by simply returning to the original documents. He will be overwhelmed with the magnitude of the Founders’ reliance on and commitment to God and Christianity.

Take, as one of a myriad of examples, an address delivered by an early President of the United States, John Quincy Adams. Not only did John Quincy live during the founding era (born in 1767), not only was his father a primary, quintessential Founder, but John Quincy was literally nurtured by his father in the vicissitudes and intricacies of the founding of the Republic. John Adams involved his son at an early age in his own activities and travels in behalf of the fledgling nation. He accompanied his father to France in 1778, became Secretary to the American Minister to Russia, was the Secretary to his father during the peace negotiations that ended the American Revolution in 1783, served as U.S. foreign ambassador, both to the Netherlands and later to Portugal, under George Washington, to Prussia under his father’s presidency, and then to Russia and later to England under President James Madison. He served as a U.S. Senator, and then Secretary of State under President James Monroe, and then as the nation’s sixth President (1825-1829), and finally as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, where he was a staunch and fervent opponent of slavery.

(born in 1767), not only was his father a primary, quintessential Founder, but John Quincy was literally nurtured by his father in the vicissitudes and intricacies of the founding of the Republic. John Adams involved his son at an early age in his own activities and travels in behalf of the fledgling nation. He accompanied his father to France in 1778, became Secretary to the American Minister to Russia, was the Secretary to his father during the peace negotiations that ended the American Revolution in 1783, served as U.S. foreign ambassador, both to the Netherlands and later to Portugal, under George Washington, to Prussia under his father’s presidency, and then to Russia and later to England under President James Madison. He served as a U.S. Senator, and then Secretary of State under President James Monroe, and then as the nation’s sixth President (1825-1829), and finally as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, where he was a staunch and fervent opponent of slavery.

Here was a man who was sufficiently intimate with the founding era to know whereof he spoke. He was there—and his life not only spanned the founding era, but was intricately intertwined with the circumstances surrounding the birth of the country. While Secretary of State, in a July 4, 1821 speech to the citizens of the nation’s capital in Washington, John Quincy Adams articulated a penetrating summary of the theological beliefs of the Founders:

From the day of the Declaration, the people of the North American Union and of its constituent States, were associated bodies of civilized men and Christians, in a state of nature; but not of Anarchy. They were bound by the laws of God, which they all, and by the laws of the Gospel, which they nearly all, acknowledged as the rules of their conduct (1821, p. 26, emp. added).

Observe: this well-qualified eye-witness to the founding of the Republic claimed that all of the Founders believed in the God of the Bible. Not an atheist among them! He further claimed that nearly all—the vast majority—of the Founders also believed in the Gospel of Jesus Christ and the Christian religion. Case closed. So who should we believe? The ACLU, the NEA, Americans United for Separation of Church and State, revisionist historians, liberal politicians, activist judges, and socialist educators—or John Quincy Adams?

REFERENCES

Adams, John Quincy (1821), Address Delivered at the request of a Committee of the Citizens of Washington on the Occasion of Reading the Declaration of Independence on the 4th of July, 1821 (Washington: Davis & Force), [On-line], URL: http://digital.library.umsystem.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?sid=b80c023f0 007f89b5b95e4be026fa267;c=jul;idno=jul000087.

American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (2000), (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin), fourth edition.

The post The Founders: Atheists & Deists or Theists & Christians? appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>The post Thomas Paine Lost His Common Sense appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>|

Courtesy of the |

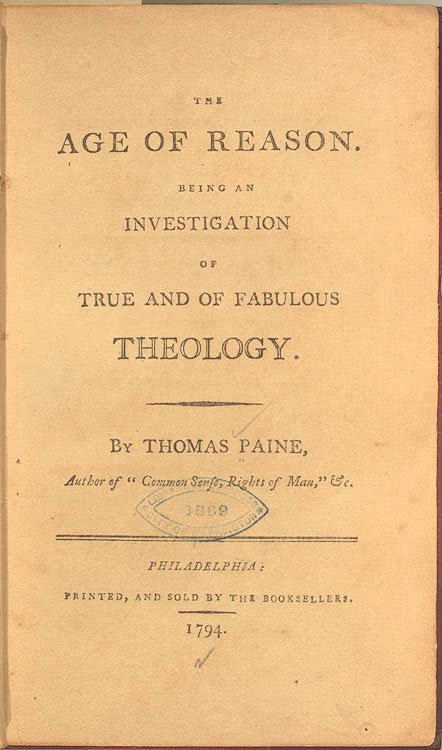

Yet, despite his significant role in the founding of America, Paine was among the small handful of Founders who were not particularly pleased with the Christian religion. Styling himself a “deist,” he is especially conspicuous for his 1794 production of The Age of Reason—a scathing denunciation of the Christian religion. Written nearly two decades after the Declaration of Independence, Paine challenged the inspiration of the Bible, denounced the formal world religions, including the abundant perversions of Christianity, and opposed the promotion of any national church or religion.

Skeptics and atheists of today like to align themselves with Paine (e.g., “Tom Paine Award…,” 2006; cf. Dawkins, 2006, p. 59). Nevertheless, Paine was not an atheist. He claimed to believe in God and afterlife: “I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life” (Paine, 1:5). He also wrote: “Were man impressed as fully and as strongly as he ought to be with the belief of a God, his moral life would be regulated by the force of that belief; he would stand in awe of God and of himself, and would not do the thing that could not be concealed from either” (2:175). Paine not only believed in “the certainty of his existence and the immutability of his power,” he asserted that “it is the fool only, and not the philosopher, or even the prudent man, that would live as if there were no God.” In fact, he stated that it is “rational to believe” that God would call all people “to account for the manner in which we have lived here” (2:173).

Paine certainly did not represent the views of the majority of his contemporaries. In fact, several of the Founders rebuked Paine for his treatise (Miller, 2005). One Founder even wrote a lengthy refutation. That Founder was the prominent and influential figure, Elias Boudinot (1740-1821). He has a long and illustrious list of achievements and capacities in service to the country. A member of the New Jersey Assembly in 1775, Boudinot served as Commissary General of Prisoners for the Revolutionary Army (1776-1779). He served in the Continental Congress (1778-1779, 1781-1784), as its President in 1782-1783. He signed the Treaty of Peace with England and was elected as a Pro-Administration candidate to the First, Second, and Third Congresses (1789-1795), when he helped frame the Bill of Rights, and was the first attorney admitted to the Supreme Court bar (1790). He was Director of the U.S. Mint (1795-1805), founding president of the American Bible Society, member of the Massachusetts Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, and president of the New Jersey Bible Society. He died on October 24, 1821 in Burlington, New Jersey and was buried in St. Mary’s Protestant Episcopal Church Cemetery (see “Boudinot, Elias,” n.d.; Boudinot, 1896).

In direct contradiction to the infidelity espoused in The Age of Reason, Elias Boudinot published a masterful rebuttal in 1801, which he titled The Age of Revelation. The title signified that, contrary to the vain machinations of fallible human reason unguided by divine insight, we humans have access to God’s revelation in His Word, the Bible. Consider a few of Boudinot’s choice remarks regarding The Age of Reason and its author (though this brief perusal is not intended to provide the reader with Boudinot’s specific rebuttals to Paine’s points).

First, throughout the treatise, Boudinot identifies Paine’s endeavor to destroy Christianity as typical of the vain attempts of skeptics in every age. He lays Paine’s errors bare, labeling them as “falsehoods and misrepresentations,” “extreme ignorance of the divine scriptures” (p. xiv), “worse than bare misrepresentation” (p. 71), “asserted with a licentious boldness, that refused the aid of proof or reason” (p. 251). The Age of Reason “must be admitted to arise, either from a total want of knowledge of the subject, or a willful perversion of the truth” (p. 71), from “either his ignorance or wickedness” (p. 131), from an “obstinate mind” (p. 209). Indeed, “truth and consistency seem to be no part of the creed of the author of the Age of Reason” (p. 158)—a “rhapsody of nonsense” (p. 247). Boudinot suggests that Paine “seems to have collected together a few technical expressions, belonging to particular subjects, and with which he seems much pleased, in hopes, that by repeating them over and over, he might persuade himself, and perhaps his readers too, that he was acquainted with the doctrines to which they were attached” (p. 72). A good summary of Boudinot’s assessment of Paine’s writing, which he suggests was “styled rather ludicrously ‘the Age of Reason,’” is seen in the following words:

Is it not on the whole, a collection of the most artful deceptions, hidden under a veil of ridicule; dangerous falsehoods, covered by an easy flow of language; and malicious sneers, made palatable by an attempt at wit and satire, that ever disgraced the pen of a pretender to philosophy, and that on a subject of infinite consequence to the essential interests of mankind? (p. 156).

In stark contrast, “True philosophy is the great supporter of the religion of Jesus Christ” (p. 156). Indeed, “take any religion but the Christian, and bring it to the test, by comparing it with the state of nature, and it will be found destitute and defenceless” (p. 157).

As if addressing himself to the evolutionists, atheists, and anti-Christian skeptics of the 21st century, Boudinot declared concerning Paine:

Had he thought proper to have used reasoning and argument, founded on proof, to enforce his observations, he might have expected a suitable reply; but when he contents himself with advancing the most palpable falsehoods and misrepresentations as facts, from which to draw the most important conclusions, and these so enveloped in sophistry, and tainted with ludicrous insinuations, as seem only calculated to impose on the young and unwary mind in matters of infinite importance, he has no right to expect any thing farther, than a positive denial of the gross misrepresentation of facts he has imposed on the public (p. 97, emp. added).

If these characterizations by Boudinot seem harsh or unloving, one must recognize the gravity and seriousness of Paine’s infidelity and the threat posed to society—a fact Boudinot well understood:

The writer of the Age of Reason, may think it harsh to be charged with falsehood in every page of his work; but it would ill become an advocate for the Gospel, not to declare it boldly, and would be doing great injustice to the cause of truth, when the everlasting interests of his fellow man are at stake; and the guilty person has no one but himself to blame for this severity, having presumed to enter on a subject with which he had not taken pains to make himself acquainted; no, not with its alphabet (p. 97, emp. added, italics in orig.).

Second, Boudinot pinpointed Paine’s primary aim, a common tactic of those who promulgate opposition to Christianity, i.e., to advance their cause by subverting the youth:

When I first took up this treatise, I considered it as one of those vicious and absurd publications, filled with ignorant declamation and ridiculous representations of simple facts, the reading of which, with attention, would be an undue waste of time…. I confess, that I was much mortified to find, the whole force of this vain man’s genius and art, pointed at the youth of America…in hopes of raising a skeptical temper and disposition in their minds, well knowing that this was the best inlet to infidelity, and the most effectual way of serving its cause, thereby sapping the foundation of our holy religion in their minds (p. xii, emp. added).

Boudinot felt that Paine’s words “are apparently designed to mislead the young and unwary mind, into the fatal vortex of skepticism and infidelity” (p. 215).

Third, those who rail against the Bible and Christianity would like their victims to believe that they have arrived at some great evidence, proof, or argument that disproves the authenticity of the Bible, the existence of God, and the Christian religion. The fact is that their assertions have all been decisively answered long ago, a point that Boudinot reiterated repeatedly to Paine:

[T]his author’s whole work, is made up of old objections, answered, and that conclusively, a thousand times over, by the advocates of our holy religion. Some of them he has endeavoured to clothe with new language, and put into a more ridiculous form; but many of them he has collected almost word for word, from the writings of the deists of the last and present century (pp. xiv-xv, emp. added).

[T]hese inefficient fragments of the writings of the last century, repeated by the late king of Prussia, Voltaire, and others, now new vamped up, with the aid of ridicule, under the title of “The Age of Reason,” and this addition, “By the Author of Common Sense,” though so often fully answered by learned men, are again introduced into the world, as new matter, in hopes of deceiving the ignorant and unwary… (p. 26, emp. added).

This author, throughout his performance, seems to have taken leave of all pretensions to modesty and decorum, or he certainly would have paid some respect to the learning and wisdom of multitudes of Christian writers and professors, who have so long and so ably defended the Christian system, against the many attacks of more formidable, as well as more modest and decent adversaries, than our author (pp. 189-199, emp. added).

Indeed, “[t]he boldness of impiety is often mistaken for knowledge” (p. xxi). It is uncanny, surreal, and deeply tragic that the last three generations of Americans have been subjected to incessant and comparable denigrations of God, the Bible, and the Christian religion through the university system of the nation, without the benefit of also receiving the decisive refutations that have been available from the beginning. Hear Boudinot:

Let me ask this man…who it is that he supposes will be alarmed by the boldness of his investigations? He must, I conclude, mean the weak and ignorant alone. What has he done to give this apprehended alarm to those who understand the subject? He had done very little more, than change the style and language of his predecessors, though they have been so fully answered (p. 250, emp. added).

Finally, Boudinot well notes that those who are sufficiently versed in the Scriptures, and the abundant evidence for the truth of the Christian religion, will remain unaffected by the propaganda of Paine and other skeptics: “To Christians, who are well instructed in the Gospel of the Son of God, such expedients rather add confirmation to their faith” (p. xiii).

As to the serious and devout Christian, who has felt the transforming power of the religion of Jesus Christ, and has experienced the internal and convincing evidence of the truth of the Divine Scriptures, the treatise referred to, will rather have a tendency to increase his faith, and inflame his fervent zeal in his master’s cause, while he beholds this vain attempt, to ridicule and set at nought, the great objects of his hope and joy, by one who plainly discovers a total ignorance of every principle of true Christianity, as revealed in the Scriptures (p. 27, emp. added).

Jesus Himself expected no one to believe Him unless He provided sufficient evidence, which He did (John 10:37). The evidence for the existence of God, the inspiration of the Bible, and the validity of the Christian religion is available to all who desire to have it. No one can stand before God on the Day of Judgment and legitimately excuse himself on the grounds of unintentional ignorance or lack of access to the evidence. Jesus declared: “If anyone wants to do His will, he shall know concerning the doctrine, whether it is from God or whether I speak on My own authority” (John 7:17). He also assured: “Ask, and it will be given to you; seek, and you will find; knock, and it will be opened to you. For everyone who asks receives, and he who seeks finds, and to him who knocks it will be opened” (Matthew 7:7-8). The Apologetics Press Web site is a storehouse of just such evidence.

Referring to the apostle Thomas in John 20:24-29, Elias Boudinot’s prayer for Thomas Paine embodies the same hopeful spirit that faithful Christians have for the unbelieving world population: “May God Almighty, of his infinite mercy, grant, that another unbelieving Thomas may be yet added to the triumphs of the cross, though it should be that despiser of the Gospel, the author of the Age of Reason himself” (p. 179).

REFERENCES

Boudinot, Elias (1801), The Age of Revelation, or, The Age of Reason Shewn To Be An Age of Infidelity (Philadelphia, PA: Asbury Dickins), http://www.google.com/books?id=XpcPAAAAIAAJ.

Boudinot, Elias (1896), The Life, Public Services, Addresses and Letters of Elias Boudinot, ed. J.J. Boudinot (New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.).

“Boudinot, Elias” (no date), Biographical Directory of the United States, http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=B000661.

Costa, Helena Rodrigues (1987), Bibliographical Supplement: A Covenanted People, the Religious Tradition and the Origins of American Constitutionalism (Providence, R.I.: John Carter Brown Library).

Dawkins, Richard (2006), The God Delusion (New York: Houghton Mifflin Books).

Miller, Dave (2005), “Deism, Atheism, and the Founders,” http://apologeticspress.org/articles/650.

Paine, Thomas (1827), The Age of Reason (New York: G.N. Devries), https://books.google.com/books?id=sqAOAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=the+age+of+reason+paine&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi48qewg7DjAhUDV80KHdk-Db4Q6AEILjAB#v=onepage&q=the%20age%20of%20reason%20paine&f=false.

“Tom Paine Award for Exemplary Service to Humanity” (2006), Atheist Foundation of Australia, September 8, http://www.atheistfoundation.org.au/tompaineaward.htm.

Wood, Gordon (2002), The American Revolution: A History (New York: Modern Library).

The post Thomas Paine Lost His Common Sense appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>The post Deism, Atheism, and the Founders appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>Were the Founders “deists”? A standard dictionary definition of the word is: “The belief, based solely on reason, in a God who created the universe and then abandoned it, assuming no control over life, exerting no influence on natural phenomena, and giving no supernatural revelation” (American Heritage…, 2000, p. 479). One would be hard-pressed to identify a Founder that fits this description. Indeed, the writings of the Founders are replete with their belief in and promotion of the Christian religion in its enlarged sense. Even Thomas Jefferson, who probably questioned the deity of Christ, nevertheless advocated and defended true Christianity. In a letter to Dr. Benjamin Rush on April 21, 1803, he wrote:

Dear Sir, In some of the delightful conversations with you, in the evenings of 1798-99, and which served as an anodyne to the afflictions of the crisis through which our country was then laboring, the Christian religion was sometimes our topic; and I then promised you, that one day or other, I would give you my views of it. They are the result of a life of inquiry & reflection, and very different from that anti-Christian system imputed to me by those who know nothing of my opinions. To the corruptions of Christianity I am indeed opposed; but not to the genuine precepts of Jesus himself. I am a Christian, in the only sense he wished any one to be; sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others (“The Thomas Jefferson Papers…,” n.d., emp. added).

Among the small handful of those who were not particularly whetted to the Christian religion, Thomas Paine is conspicuous, especially in his production of Age of Reason. Though he challenged the inspiration of the Bible, denounced the formal world religions, including the perversions of Christianity that were in abundance, and opposed the promotion of any national church or religion, nevertheless he was not an atheist. He claimed to believe in God and afterlife: “I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life” (1794). He also wrote: “Were man impressed as fully and as strongly as he ought to be with the belief of a God, his moral life would be regulated by the force of that belief; he would stand in awe of God and of himself, and would not do the thing that could not be concealed from either” (1794). Paine not only believed in “the certainty of his existence and the immutability of his power,” he asserted that “it is the fool only, and not the philosopher, or even the prudent man, that would live as if there were no God.” In fact, he stated that it is “rational to believe” that God would call all people “to account for the manner in which we have lived here” (1794).

Nevertheless, Paine styled himself a “deist” and hurled some rather uncomplimentary epithets against the Christian religion. But the real issue—one that has been largely ignored by the revisionist historians of the last fifty years—is whether Paine’s views were representative of the Founders and the citizenry of America at the time. The historical record proves that they were not. In fact, Paine’s production of Age of Reason nearly two decades after the Declaration of Independence drew heavy fire from several of the Founders who expressed strong aversion to Paine’s ideas in no uncertain terms. Consider the following examples.

John Adams played a central role in the birth of our nation, as evidenced by a string of significant participatory activities, including delegate to the Continental Congress (1774-1777) where he signed the Declaration of Independence, signer of the peace treaty that ended the American Revolution (1783), two-time Vice-President under George Washington (1789-1797), and second President of the United States (1797-1801). Yet, Adams’ sentiments regarding Paine’s writing were, to say the least, blunt: “The Christian religion is, above all the religions that ever prevailed or existed in ancient or modern times, the religion of wisdom, virtue, equity and humanity, let the Blackguard Paine say what he will” (3:421, 1856). “Blackguard” was an 18th century term for a thoroughly unprincipled person—a scoundrel.

Zephaniah Swift, who was a member of the U.S. Congress from 1793-1797, offered a strong reaction to Paine:

[W]e cannot sufficiently reprobate the beliefs of Thomas Paine in his attack on Christianity by publishing his Age of Reason…. He has the impudence and effrontery to address to the citizens of the United States of America a paltry performance which is intended to shake their faith in the religion of their fathers…. No language can describe the wickedness of the man who will attempt to subvert a religion which is a source of comfort and consolation to its votaries merely for the purpose of eradicating all sentiments of religion (1796, 2:323-324).

John Jay was another brilliant Founder with a long and distinguished career in the formation and shaping of American civilization from the beginning. He not only was a member of the Continental Congress from 1774-1776, serving as President from 1778-1779, he also helped to frame the New York State Constitution and then served as the Chief Justice of the New York Supreme Court. He co-authored the Federalist Papers, was appointed as the first Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court by George Washington (1789-1795), served as Governor of New York (1795-1801), and was the vice-president of the American Bible Society (1816-1821). In a letter dated February 14, 1796, he affirmed:

I have long been of the opinion that the evidence of the truth of Christianity requires only to be carefully examined to produce conviction in candid minds, and I think they who undertake that task will derive advantages…. As to The Age of Reason, it never appeared to me to have been written from a disinterested love of truth or of mankind (Jay, 1833, 2:266).

Several of the Founders were severe in their denunciations of Paine. John Witherspoon, member of the Continental Congress (1776-1782) and signer of the Declaration of Independence, insisted that Paine was “ignorant of human nature as well as an enemy to the Christian faith” (1802, 3:24). Another signer of the Declaration, Charles Carroll, pronounced Paine’s work as “blasphemous writings against the Christian religion” (as quoted in Gurn, 1932, p. 203). Yet another Declaration signer, Benjamin Rush, called The Age of Reason “absurd and impious” (1951, 2:770). William Paterson, signer of the federal Constitution and U.S. Supreme Court justice appointed by George Washington, became so indignant over those few Americans who seemed to agree with Paine, that he declared: “Infatuated Americans, why renounce your country, your religion, and your God? Oh shame, where is thy blush? Is this the way to continue independent, and to render the 4th of July immortal in memory and song?” (as quoted in O’Conner, 1979, p. 244). [NOTE: Observe that Paterson believed that independence depended on loyalty to the Christian religion and God.] In a similar vein, John Quincy Adams, referring to Paine’s Rights of Man, insisted that “Mr. Paine has departed altogether from the principles of the Revolution” (1793, p. 13). Patrick Henry asked: “What is there in the wit, or wisdom of the present deistical writers or professors…? And yet these have been confuted, and their fame decaying; in so much that the puny efforts of Paine are thrown in, to prop their tottering fabric, whose foundations cannot stand the test of time” (as quoted in Wirt, 1817, pp. 386-387, emp. added; cf. Arnold, 1854, p. 250), and the President of the Continental Congress, Elias Boudinot, published The Age of Revelation in direct rebuttal to The Age of Reason (1801).

Even Benjamin Franklin, one of the least religious of the Founding Fathers, though a longtime friend of Paine, viewed Paine’s thinking with great disfavor, as evidenced by Franklin’s critique of a previous manuscript written by Paine:

I have read your Manuscript with some Attention. By the Arguments it contains against the Doctrine of a particular Providence, tho’ you allow a general Providence, you strike at the Foundation of all Religion: For without the Belief of a Providence that takes Cognizance of, guards and guides and may favour particular Persons, there is no Motive to Worship a Deity, to fear its Displeasure, or to pray for its Protection. I will not enter into any Discussion of your Principles, tho’ you seem to desire it; At present I shall only give you my Opinion that tho’ your Reasonings are subtle, and may prevail with some Readers, you will not succeed so as to change the general Sentiments of Mankind on that Subject, and the Consequence of printing this Piece will be a great deal of Odium drawn upon your self, Mischief to you and no Benefit to others. He that spits against the Wind, spits in his own Face. But were you to succeed, do you imagine any Good would be done by it?…. I would advise you therefore not to attempt unchaining the Tyger, but to burn this Piece before it is seen by any other Person, whereby you will save yourself a great deal of Mortification from the Enemies it may raise against you, and perhaps a good deal of Regret and Repentance. If Men are so wicked as we now see them with Religion what would they be if without it? I intend this Letter itself as a Proof of my Friendship…. (1840, 10:281-282, emp. added).

Sadly, friendless and shunned due to his irreligious views, Thomas Paine died in Greenwich Village, New York City, on June 8, 1809. At the time of his death, most U.S. newspapers reprinted the obituary notice from the New York Citizen, which read in part: “He had lived long, did some good and much harm.” Only six mourners came to his funeral (Conway, pp. 417-418).

The overwhelming majority of the Founders and the bulk of the American population at the beginning of our nation held strong convictions regarding the primacy of the Christian religion over all other religions (as well as no religion at all). What a change has come over the country. God has blessed America in the past—undoubtedly due to the willingness of the Founders and the citizenry to acknowledge Him as the one true God and Author of the one true religion. Now that so many are rejecting the one true God, while accommodating false religions and ideologies, we can well expect that the bestowal of God’s blessings on our national well-being will come to an end. In the words of George Washington:

I am sure there never was a people who had more reason to acknowledge a Divine interposition in their affairs than those of the United States; and I should be pained to believe that they have forgotten that Agency which was so often manifested during our revolution, or that they failed to consider the omnipotence of that God who is alone able to protect them (1838, 10:222-223).

The psalmist was even plainer: “The wicked shall be turned into hell, and all the nations that forget God” (Psalm 9:17).

REFERENCES

Adams, John (1856), The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States, ed. Charles Adams (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, & Co.).

Adams, John Quincy (1793), An Answer to Pain’s [sic] “Rights of Man” (London: John Stockdale).

American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (2000), (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin), fourth edition.

Arnold, S.G. (1854), The Life of Patrick Henry of Virginia (Buffalo, NY: Miller, Orton, & Mulligan).

Boudinot, Elias (1801), The Age of Revelation, or, The Age of Reason Shewn To Be An Age of Infidelity (Philadelphia, PA: Asbury Dickins).

Conway, Moncure (1909), The Life of Thomas Paine (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons).

Franklin, Benjamin (1840), The Works of Benjamin Franklin, ed. Jared Sparks (Boston, MA: Tappan, Whittemore, & Mason).

Gurn, Joseph (1932), Charles Carroll of Carrolton (New York: P.J. Kennedy & Sons).

Jay, William (1833), The Life of John Jay (New York: J.&J. Harper).

O’Connor, John (1979), William Paterson: Lawyer and Statesman (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press).

Paine, Thomas (1794), Age of Reason, [On-line], URL: http://www.ushistory.org/paine/reason/singlehtml.htm.

Rush, Benjamin (1951), Letters of Benjamin Rush, ed. L.H. Butterfield (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

Swift, Zephaniah (1796), A System of Laws of the State of Connecticut (Windham, CT: John Byrne).

“The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1. General Correspondence. 1651-1827” (no date), Library of Congress, [On-line], URL: http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mtj1&fileName=mtj1page028.db& recNum=190&itemLink=%2Fammem%2Fcollections%2Fjefferson_papers%2Fmtjser1. html&linkText=6.

Washington, George (1838), The Writings of George Washington, ed. Jared Sparks (Boston, MA: Ferdinand Andrews).

Wirt, William (1817), Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (Philadelphia, PA: James Webster).

Witherspoon, John (1802), The Works of Reverend John Witherspoon (Philadelphia, PA: William Woodard).

The post Deism, Atheism, and the Founders appeared first on Apologetics Press.

]]>